More than a century after 48 000 people died in concentration camps in what’s known as the South African War between 1899 and 1902 – or the Anglo-Boer War – the events of that period are back in the headlines.

The camps were established by the British as part of their military campaign against two small Afrikaner republics: the ZAR (Transvaal) and the Orange Free State.

The scandalous campaign is back in the news following controversial comments by British Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg on a BBC television programme.

Rees-Mogg’s statements have caused consternation because they were riddled with inaccuracies. It’s time to set the record straight and to refute his inaccuracies one by one. I do this based on the historical research I’ve done on the South African War for the last 49 years.

Setting the record straight

The claim that caused the most upset was Rees-Mogg’s allegation that the concentration camps had exactly the same mortality rate as was the case in Glasgow at the time.

This is simply factually incorrect.

In its recent Glasgow Indicators Project the Glasgow Centre for Population Health gives the death rate of people in the city as 21 per 1000 per annum in 1901.

The death rate for Boer civilians in the concentration camps in South Africa exceeded this by a factor of 10. It’s well established that 28 000 white people and 20 000 black people died in various camps in South Africa. Between July 1901 and February 1902 the rate was, on average, 247 per 1000 per annum in the white camps. It reached a high of 344 per 1000 per annum in October 1901 and a low of 69 per 1000 per annum in February 1902.

The figures would have been even higher had it not been for the fact that British welfare campaigner Emily Hobhouse exposed the deplorable conditions in the camps. A subsequent report by the Government’s Ladies Commission prompted the British Government to improve conditions. Another factor that reduced the fatality rate was that Lord Milner, High Commissioner for South Africa and Governor of the Cape Colony, took over administration of the camps from the military from November 1901.

Rees-Mogg also revealed his total lack of understanding why the British military authorities established the concentration camps in statements such as:

Where else were people going to live when … (the Boers were fighting the war)?

People were put in camps for their protection.

They were interned for their safety.

They were being taken there so that they could be fed because the farmers were away fighting the Boer War.

The reality was very different.

The origins of the camps

After Lord Roberts, chief commander of the British forces, occupied the Free State capital, Bloemfontein, on 13 March 1900, he issued a proclamation inviting the Boers to lay down their arms and sign an oath of neutrality. They would then be free to return to their farms on the understanding that they would no longer participate in the war.

Eventually about 20 000 Boers – about a third – made use of this offer. They were called the “protected burghers”. Roberts had banked on this policy to end the war. But after the British occupation of the Transvaal capital, Pretoria, on 5 June 1900, there was no end in site. On the contrary, the Boers had started a guerrilla war, which included attacks on railway lines.

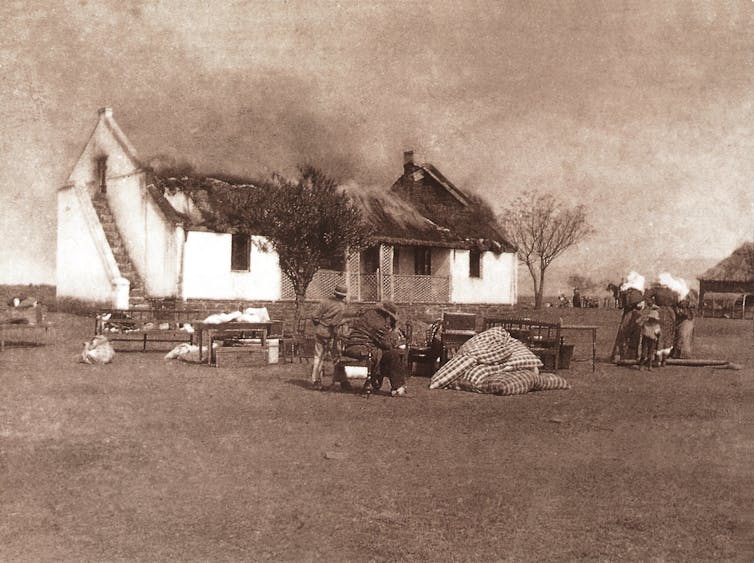

In reaction Roberts issued a proclamation on 16 June 1900, stating that, for every attack on a railway line the closest homestead would be burnt down. This was the start of the scorched earth policy. When this didn’t work, Roberts issued another proclamation in September stating that all homesteads would be burnt in a radius of 16 km of any attack, and that all livestock would be killed or taken away and all crops destroyed.

This policy was intensified dramatically when Lord Kitchener took over from Roberts as commander in November 1900. Homesteads and whole towns were burnt down even if there was no attack on any railway. In this way almost all Boer homesteads – about 30 000 in all – were razed to the ground and thousands of livestock killed. The two republics were entirely devastated.

Meanwhile the Boer leaders were reorganising their commandos after some major setbacks. One action was to remobilise the Boers who had laid down their arms.

Roberts felt he should protect his oath takers and gather them in refugee camps. The first two were established in Bloemfontein and Pretoria in September 1900.

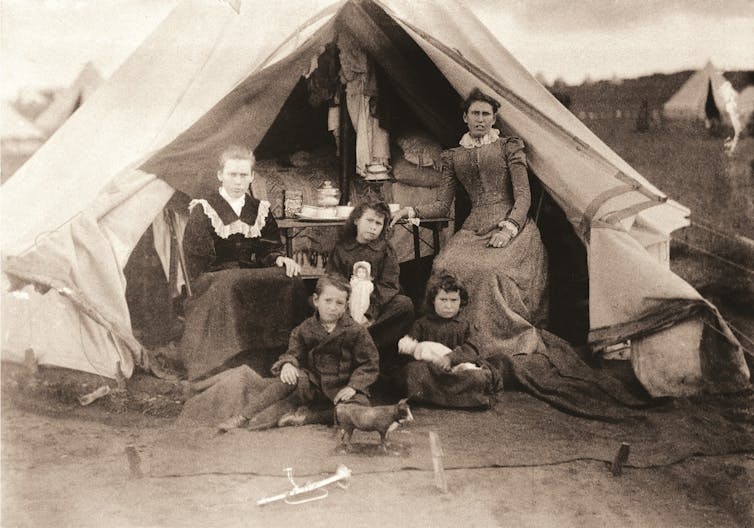

But the scorched earth policy had led to more and more Boer women and children being left homeless. Roberts decided to bring them into the camps too. They were called the “undesirables” – families of Boers who were still on commando or already prisoners of war. They were given fewer rations than others in the camps.

These families eventually outnumbered the protected burghers and their families by 7:3.

These families were taken against their will. They were forcibly put on ox wagons and open railway trucks and taken to the camps. They were not, as Rees-Mogg claimed, moved for their protection and safety. Nor were they moved to the camps to be fed. Rather, their internment had everything to do with ending the resistance of Boers still fighting the British.

The administration of the camps was appalling. Food was of a very poor quality, sanitation deplorable, tents were overcrowded and medical assistance shocking. Little was known at the time about how to handle epidemics of measles and typhoid.

This isn’t all. Rees-Mogg is also obviously unaware of the action that the British commanders took against black South Africans. A total of 66 black concentration camps where set up across the Transvaal and Free State where conditions were just as bad and the death rates similar.

These camps were set up to get black people off the land so that the Boers couldn’t get supplies from them. In addition, forcing black farmers off their land also enabled the British to use black men as labourers on gold mines.

Rees-Mogg was right on one point: the concentration camps didn’t have the same aims as Adolf Hitler’s extermination camps during the Second World War. The aim in South Africa wasn’t systematic murder.

But this shouldn’t detract from his numerous other falsehoods.![]()

Fransjohan Pretorius, Emeritus professor of History, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.