China’s involvement in many parts of Africa is expanding. Several milestones have been reached in recent years. These include China becoming the continent’s largest trading partner in 2009 and the opening of the country’s first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017.

So it’s not surprising that this has become an ever-expanding topic for both the media and researchers. But the accuracy of work being done, particularly in terms of reportage, leaves a great deal to be desired.

Over the past ten years media scholars have increasingly begun to turn their attention to the issue. It’s one of the reasons for the 2009 launch of the Africa-China Reporting Project at the University of the Witwatersrand, where I’m associated. More recently scholarly work has been produced in a bid to identify what’s missing.

In analysis I did for a recently co-authored chapter in New Directions in Africa–China Studies we argue that a number of factors have contributed to coverage of the relationship between China and African countries, at times becoming a fertile area for propaganda, misinformation and disinformation. The main factors are the pressure on journalists for fast-paced information gathering. And the second is the impact that platforms such as Google, Facebook and Twitter are having on the dissemination of news, including the growing trend of the misuse of information.

Search a topic in the widely reported area of China in Africa, and it’s clear that many of the “facts” made available often appear contradictory. China is frequently framed and referred to in binary terms. It’s either portrayed as predator, or as a friend.

But the truth is far more nuanced. Individual relationships between China and particular countries differ. It’s also true that relationships between Beijing and certain regions have different hues. On top of this, these various relationships have been moulded over time.

There are ways to address the gaps in coverage and dearth of context. But it will require support as well as concerted effort on the part of journalists and media houses in African countries to report on behalf of Africans.

No nuance

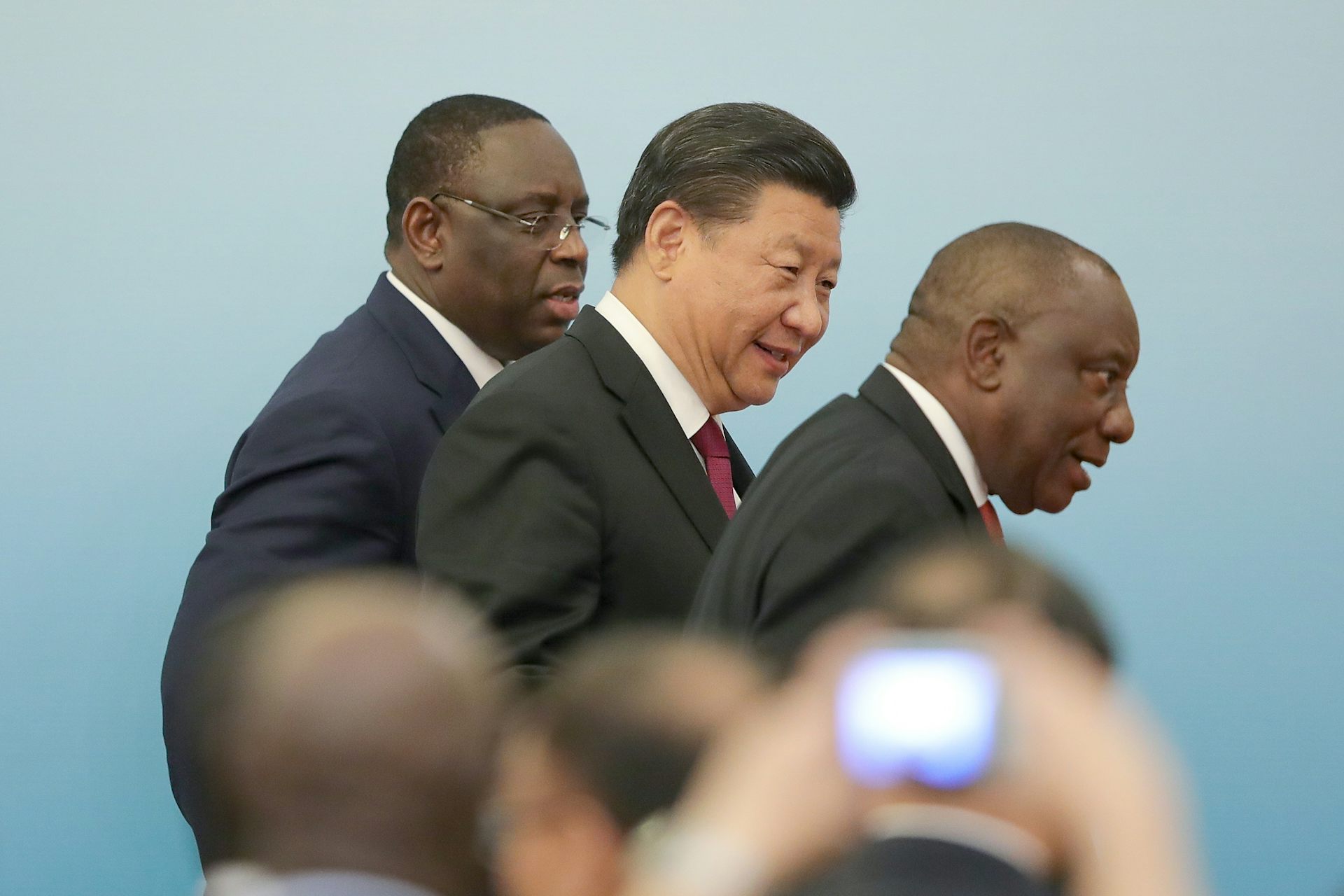

The “predator” coverage portrays African countries as “set to burn as debt soars”. The “friend” image is portrayed through coverage of officials rejecting this view, as they did at last year’s Forum on China-Africa Cooperation.

Other examples include China being portrayed as “grabbing land” in Africa, and offering “rogue aid”. On the other hand reports tend to speak about “Chinese-funded” transport infrastructure projects without acknowledgement of the fact that a myriad international and local partners are also involved.

These over-simplified and overarching “China-Africa” narratives are deeply misleading. They make extracting facts about the China-Africa relationship extremely challenging: very often opinion trumps verification.

What affects reporting?

I have established three reasons why certain narratives take hold in the popular psyche and become representative of this complex relationship.

The first relates to the issue of perceptions towards China. Perceptions about China are coloured by social and historical contexts. For example, business or government officials who have engaged with China for a longer period of time are more likely to view it in a more nuanced and even positive way.

The second factor is linked to interest. For example, those who have something to lose from China’s role in Africa may harbour more negative views. And those who have something to gain are more likely to push a positive line.

The problem is that most of the time reporting doesn’t make clear why particular individuals, or groups, hold certain views. For example, those who have a stake in the direction of links between China and a particular country, would want to push their view. Not explaining their particular interest can leave an incomplete and misguided impression. So a single perspective can multiply to become the defining narrative of a story.

The third aspect is related to a lack of understanding. The focus on Asia studies in African higher education institutions remains limited. This includes deeper understanding of the rich history, culture and complexities of the East Asia region. In contrast the US, one of China’s main global competitors, has a long tradition of Asia studies and exchanges.

Where to from here?

Part of the reason stories may be misreported is that data and information about particular relationships, particularly related to high-level agreements and deals, are missing.

This was highlighted when the Democratic Alliance, South Africa’s main opposition party, threatened to take legal action against power utility Eskom, if it did not make its 2018 loan agreement with China public. Hence links with China is also at times, a backdrop to deeper domestic interactions.

The advent of technology and the information age has brought societies closer together. But they have also reinforced persistent differences based on perception, interests and limited understanding.

The divisive views and reporting such as the Africa-China example won’t dissipate unless journalists continually ask “why” when they are presented information about China and Africa’s relations.

They also have a duty to stand back and not perpetuate the preferred flavour of the news cycle.

For their part, media houses should make sure that their journalists are better equipped to cover these complex relationships. Given that one of the trends that stands out is that reporting on the relationship between China and African countries takes place from outside the continent, it’s imperative that more on-the-ground reporting, verification and support for local journalists is encouraged.![]()

Yu-Shan Wu, Research Associate, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.