In recent months, persistent protesters in Algeria and Sudan have faced down government repression to depose long-time political leaders. Unfortunately, these two countries are the exception rather than the norm.

More often than not, political opposition in countries across the continent has met a different fate as governments have used a variety of tactics to restrict freedoms and dissent. These include shutting down the internet (Cameroon, Zimbabwe), imposing social media taxes (Uganda), and imposing blogger licenses (Tanzania). Governments have also resorted to outright violence in Burundi, Senegal, Togo and Zambia.

Freedom House’s 2019 Freedom in the World Report suggests that political liberalisation in countries like Ethiopia and The Gambia belies “creeping restrictions” and a general trend toward authoritarian behaviour.

This trend is confirmed in the most recent survey conducted by Afrobarometer, an independent African research network. It was conducted between late 2016 and late 2018 in 34 countries. On average across all the countries surveyed, citizens appeared to confirm that civic and political space was closing. Many also expressed a willingness to accept restrictions on their liberties in the name of security.

Shrinking political space

Two-thirds (67%) of the respondents said they were at least “somewhat” free to say what they thought. This represents a 7 percentage point decline across 31 countries tracked since 2011/2013.

When it came to the freedom to discuss politics, the picture was more troubling: 68% felt that they needed to be careful about what they said. Across a sample of 20 countries tracked over the past decade, expressions of caution had increased by 9 percentage points.

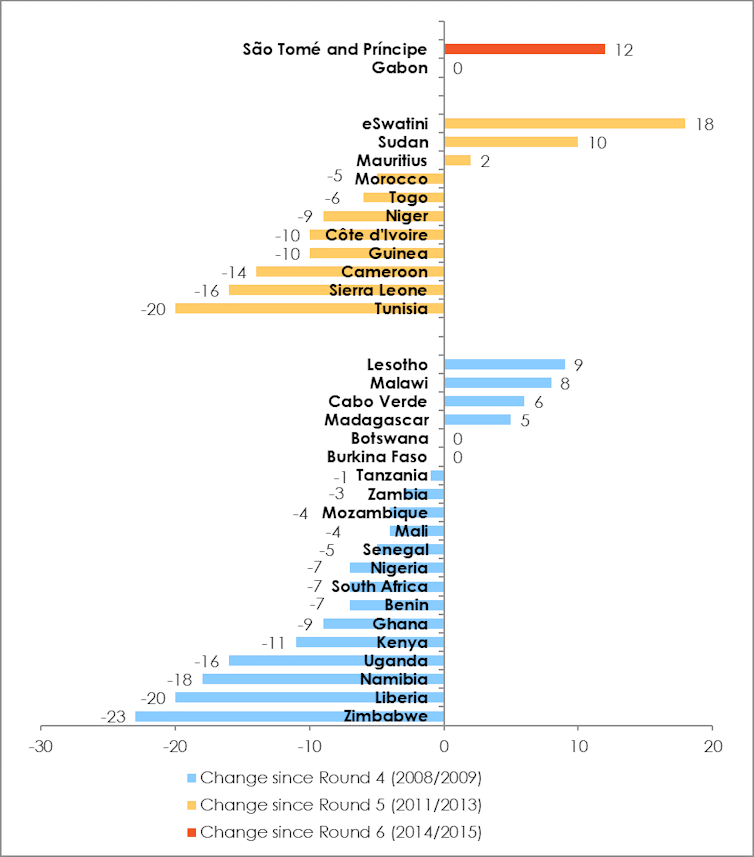

If freedom is weakening, so is popular demand for it. Six in ten respondents (62%) believed that citizens should be able to join any political organisation they choose. Yet, popular insistence on freedom of association declined by at least 3 percentage points in 21 of the surveyed countries. It grew in just seven countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in support for freedom to join any organisation (percentage points) | 33 countries | 2008-2018

In Gabon and Togo more than 80% of citizens rejected the idea that the government should have the right to ban organisations that went against its policies. In both countries growing popular discontent with political processes was met with government efforts to repress discontent.

In contrast, in Tanzania just 39% of citizens favoured full freedom of association. The government in Tanzania has recently taken steps to close political space. Likewise, there was some underlying support in Kenya for increasing efforts of social control. Only 47% of respondents supported freedom of association.

Individual freedoms versus security?

A second troubling trend was the considerable willingness to accept government restrictions on individual freedoms in the name of public security. For example, a slim majority (53%) of respondents stood for people’s right to private communication. But a substantial minority (43%) were willing to accept that governments should be able to monitor private communications to make sure that people weren’t plotting violence. This included monitoring their cellphones.

More than two-thirds supported the right to private communication in Zimbabwe, Gabon, and Sudan, all countries where civil liberties are still contested. But only about one-third or less of citizens in Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Tanzania, Senegal, and Mali opted for freedom over security when it came to private communication.

Forty-nine percent of respondents favoured complete freedom of religious speech, while 47% thought the government should be able to regulate what was said in places of worship. The lowest levels of support for religious freedom came from Tunisia (21%), Mali (23%), and Senegal (31%). (Both Mali and Tunisia have experienced major incidents of extremist violence.)

Support for freedom of movement is even less robust. Only about one in three Africans (35%) said that even when their country is faced with security threats,

people should be free to move about the country at any time of day or night.

Political liberalisation

Since these trends in demand for and supply of freedoms vary considerably by country, more detailed country-level analysis would be instructive. Looking in particular at countries that have experienced significant political liberalisation in recent years, we found that Gambians generally embraced freedoms of association, communication, and speech in religious settings. But they supported the idea that the government should be able to impose curfews and roadblocks.

In contrast, in Burkina Faso and Tunisia, the majority of people supported government monitoring of private communications, regulation of religious speech, and restrictions on free movement, with average support for freedom of association.

These levels of support for government restrictions in Burkina Faso and Tunisia are concerning, given that political liberalisation in both countries is relatively recent and still vulnerable.

In Zimbabwe, where the new government has argued that a “new dispensation” is afoot since the ousting of former President Robert Mugabe, citizens generally embraced basic freedoms, and saw no change in the level of freedom of expression over the past decade.

But Zimbabweans expressed high levels of caution about exercising basic freedoms, suggesting scepticism about the government’s gestures toward political liberalisation.

Finally, more established democracies presented a mixed picture. On the one hand, citizens in Cabo Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe generally embraced basic freedoms. They also rejected restrictions on freedoms because of perceived security threats. Yet, the high degree of tolerance for restrictions on basic freedoms in Ghana highlights the power – across much of Africa – of the security argument for restricting individual freedoms.![]()

Peter Penar, Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science, Michigan State University and Carolyn Logan, Deputy Director of the Afrobarometer & Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and MSU’s African Studies Center, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.