The purpose of national economic reform is to change the structure and overall direction of an economy. Reforms therefore can affect the amount of resources available to a country. They can also affect human rights.

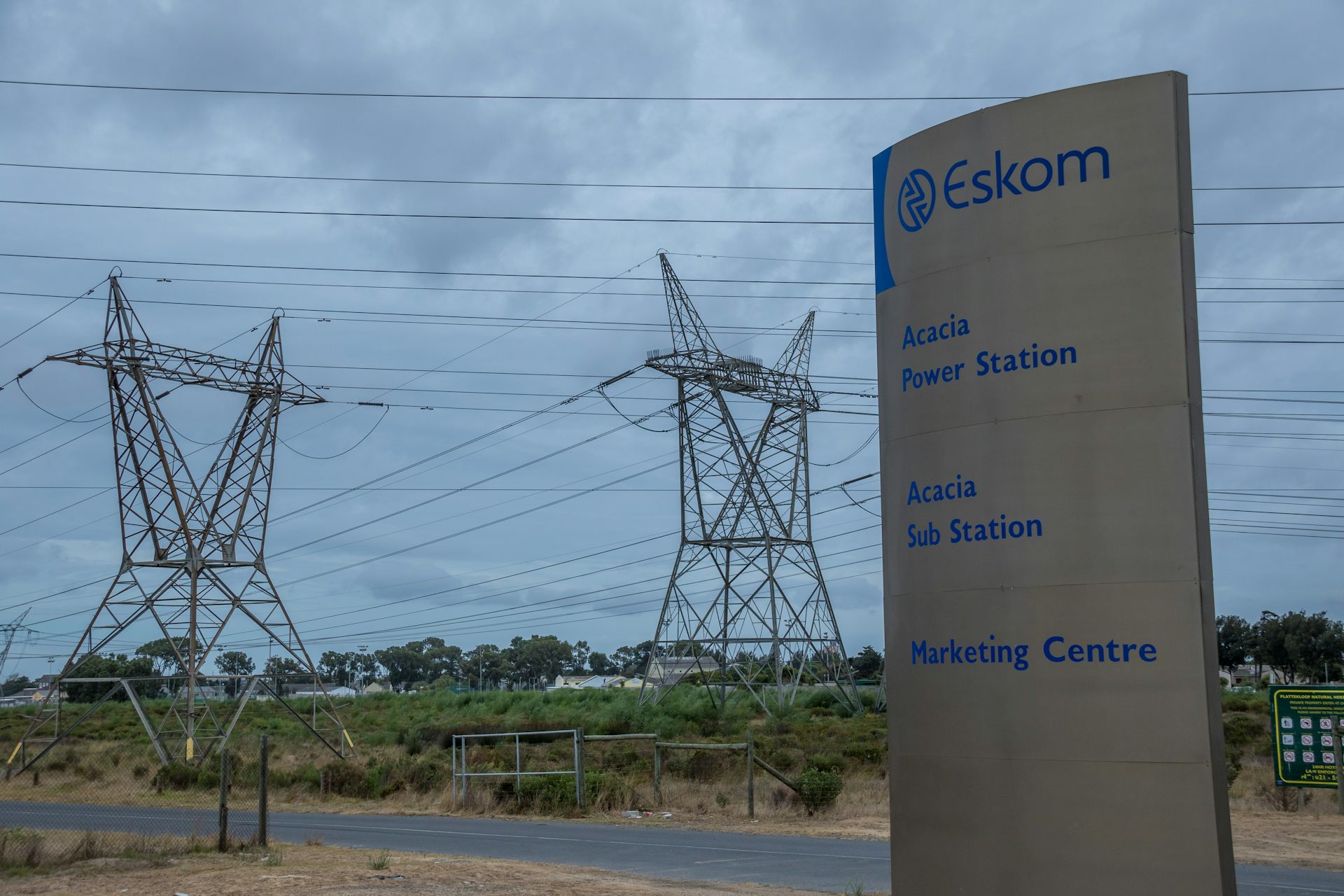

South Africa desperately needs to reform its economy. Its capacity to deal with its tragic problems of unemployment, poverty and inequality is diminishing. State owned enterprises like the power utility Eskom, public transport group Prasa and South Africa Airways, are failing to deliver adequate services. They are also draining public resources away from more productive and socially beneficial purposes.

And the country’s economy is too carbon intensive. It needs to transition to less carbon intensive forms of production and consumption.

The South African government’s proposed responses to these challenges are controversial. They involve job losses and cuts in social services. Government claims that over time the reforms will yield more jobs, better services and a growing economy that is environmentally sustainable. Unfortunately, while the short term costs are clear, the long term benefits are uncertain. Even if they arrive, they may not benefit the groups bearing the short term losses.

The same is true about the alternatives. For example, the mining sector’s efforts to protect the coal industry may preserve jobs but at the cost of the long term health of children. Efforts by trade union to preserve wages for public sector workers may mean fewer jobs in the public sector for today’s students and learners.

In short, all these options may produce substantial benefits. But they may also exacerbate social conflict and not generate the promised benefits.

Mitigating risks

What can government do to mitigate the risks and maximise the chances of an outcome that is economically productive and socially and environmentally sustainable? What can be done to minimise social dislocations?

Government should develop a good understanding of how each of the different proposals will affect different groups in society – today and over the life of the reforms. This cannot be done merely through dialogue and speculation. It requires impact assessments of each reform option before its implemented.

Such impact assessments are standard operating practice for large projects. Their scope has expanded over time. They now include environmental, social, health and, more recently, human rights elements.

International best practice standards have been developed for different actors. For example, the financial sector has developed the Equator Principles. The International Council of Mining and Minerals has a new set of Mining Principles. More generally applicable principles including the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the International Organization for Standardization’s standards on environmental management, sustainability and social responsibility.

There are growing demands for similar impact assessments of substantial government policy initiatives.

Measuring impact on rights

In 2019, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution encouraging all states, national human rights institutions and non-state actors to use the Guiding Principles on Human Rights Impact Assessment of Economic Reforms when developing economic reforms. These principles were developed by the UN’s Independent Expert on Foreign Debt and Human Rights.

The Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria has developed a user friendly guide to the 22 guiding principles for governments and civil society groups in the 15 countries that belong to the Southern African Development Community.

The principles begin with an overview of the binding human rights obligations that states assumed by signing and ratifying the international human rights conventions.

These treaties oblige governments to respect, protect and fulfil the human rights of people under their jurisdiction. They should ensure that their economic reform efforts promote and do not undermine human rights. This means that governments must implement reforms that are non-discriminatory. These reforms must also allocate the maximum available resources to the realisation of the rights of all people in a country.

Where governments cannot avoid adopting policies that have an adverse effect on human rights, they must ensure that their actions are necessary, proportionate, reasonable, non-discriminatory. They must also ensure that such policies are designed to contribute to the ultimate realisation of human rights.

The guiding principles also specify that governments should ensure that their proposed reform policies are assessed for their impact on human rights. These impact assessments should assess the short, medium and long term impacts of the proposed policies. They should also be based on the principles of participation, access to information and accountability.

The aim is to promote a national dialogue about the proposed policies. The Guiding Principles are flexible about who, inside or outside the government, should undertake these impact assessments. However, the assessors must be credible, independent and technically competent and the impact assessments must inform policymaking.

Time to act

Even before the UN’s guiding principles were adopted, governments and non-state actors began assessing economic reform initiatives for their impact on human rights. For example, Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission assessed the impact on human rights of the proposed US-Thailand Free Trade Agreement. The UN Economic Commission for Africa, the UN Office of the High Commission for Human Rights and the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung jointly commissioned a human rights assessment of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement. The government of Scotland conducts an annual equality impact assessment of its budget. And the Center for Economic and Social Rights has coordinated human rights impact assessments of austerity programmes in Brazil, South Africa and Spain.

South Africa’s Social and Economic Impact Assessment System requires government to assess the socioeconomic impact of proposed policy initiatives, legislation and regulation before they are submitted to cabinet for approval. It is unclear if such an assessment has been done of current economic reform proposals.

The government should do this assessment and should release it for public comment and review. But there’s no reason for non-state actors to wait for government to act. Social organisations, representing business, labour and civil society can conduct their own impact assessments. This will inform the debate about the economic reform strategy that South Africa should adopt.![]()

Danny Bradlow, SARCHI Professor of International Development Law and African Economic Relations, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.