It’s been 20 years since the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation was first held. Another summit is planned for September 2021 in Dakar, Senegal. Meanwhile, Chinese and African officials are reviewing and reflecting on their two-decade relationship.

China’s growing engagement with Africa has had a positive, albeit uneven, effect on Africa’s economic growth, economic diversification, job creation and connectivity.

China-Africa relations are mostly organised via government to government relations. But the perceptions and wellbeing of ordinary people also need to be better considered.

In 2016 the pan-African research institute Afrobarometer published its first study on what Africans think of their governments’ engagement with China.

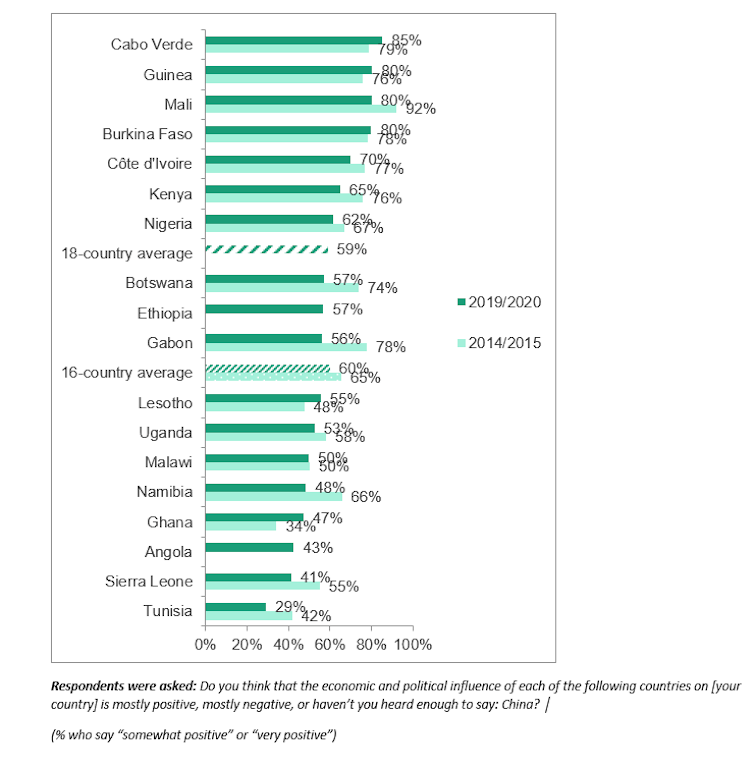

The study found that 63% of citizens surveyed from 36 countries generally had positive feelings towards China’s assistance. Some things that stood out were China’s infrastructure, development, and investment projects in Africa. On the flip side, perceptions of the quality of Chinese products tarnished the country’s image.

In 2019/20, Afrobarometer conducted another wave of surveys. Data from 18 countries – gathered face-to-face from a randomly selected sample of people in the language of the respondent’s choice – was collected before the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey questions covered how Africans perceive Chinese loans, debt repayments, and Africa’s reliance on China for its development.

Preliminary findings show that the majority of Africans still prefer the US over China as a development model, that China’s influence is still largely considered as positive for Africa, and that Africans who are aware of Chinese loans feel that their countries have borrowed too much.

This is important because – as both African and Chinese leaders reflect on their engagement – these findings should allow them to build a forward-looking relationship that better reflects African citizens’ opinions and needs.

US vs China

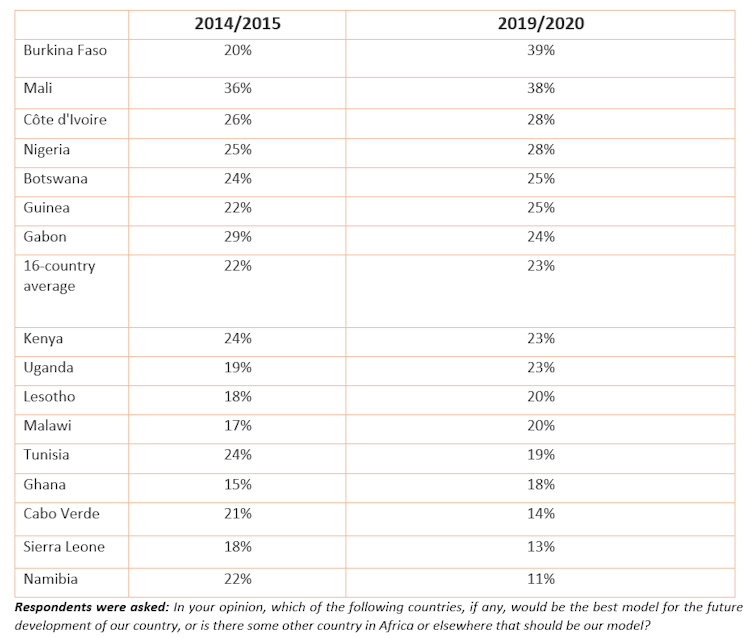

The surveys found that Africans still prefer the American development model over the Chinese one. The Chinese development model hinges on state-led policy planning while the American model emphasises the importance of the free market.

Across the 18 countries surveyed, 32% preferred the American development model, while 23% preferred the Chinese model. Overall, this hasn’t changed much since 2014/15, but a few country-level shifts emerge.

In Lesotho and Namibia, the US has surpassed China as a preferred development partner. In Burkina Faso and Botswana, China is preferred. Angolans and Ethiopians, who were not included in the 2014/15 survey, are partial to the American model. However, 57% of Ethiopians and 43% of Angolans believe that China’s influence is having a positive impact on their countries.

Analysts have argued that the Chinese development model is dynamic and multifaceted. It has changed over time depending on the context and period. African governments need to decide what aspects of the Chinese model are best for their countries.

A closer look at responses from the 2014/15 and 2019/20 surveys shows that in countries where China has invested mainly in infrastructure, perceptions have held steady or become more positive. This includes Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire.

China’s popularity rises in the Sahel

Perceptions of China have changed for the better in some countries in the Sahel region. Some of these countries are among the most neglected and conflict-ridden in the world.

Strategically, China has been deeply involved in security and development activities, infrastructure projects connected to the Belt and Road Initiative, and peace and security operations in the region.

In Burkina Faso, for example, the popularity of China’s development model has almost doubled, from 20% to 39%, in the five years since the previous survey.

In Guinea, where Chinese companies are mainly involved in mining projects, 80% of citizens perceive China’s economic and political influence as positive – four percentage points up from five years ago. Overall, China’s growing involvement in the Sahel region seems to have had a strong impact on citizens’ views.

Economic fortunes and debt repayment

A majority of African citizens say China’s economic activities have “some” or “a lot” of influence on their countries’ economies. But the perceived influence has declined from 71% in 2014/15 to 56% in 2019/20 across the 16 countries surveyed in both rounds.

And while six in 10 Africans see China’s influence on their country as positive, this perception has declined from 65% to 60% across 16 countries. Instead, regional African powers, regional and United Nations organisations, and Russia scored well in perceived positive influence. Russia was perceived well by 38%.

This could be a reflection of Russia’s growing political, economic, and security engagement with Africa, as well as the role of Russian media such as Russia Today and Sputnik. A recent study on digital media content in francophone West Africa revealed how the digital content these media houses produce quickly seeps into African media spaces.

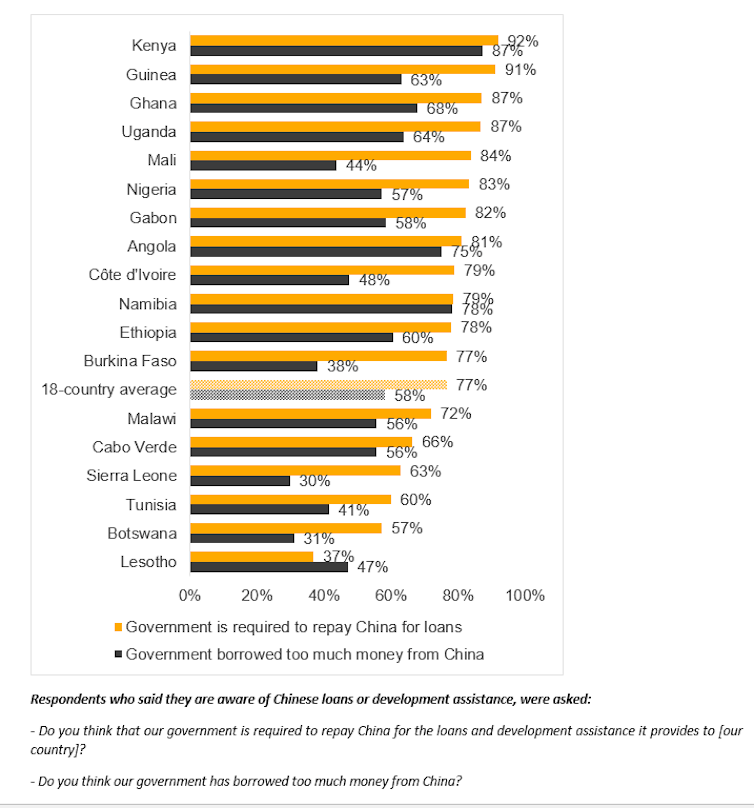

The Afrobarometer survey revealed that less than half (48%) of African citizens are aware of Chinese loans or financial assistance to their country.

Among those who said they were aware of Chinese assistance, more than 77% were concerned about loan repayment. A majority (58%) thought their governments had borrowed too much money from China.

In countries which received the most Chinese loans, citizens expressed worry about indebtedness. This included Kenya, Angola and Ethiopia. In those countries, 87%, 75%, and 60% of citizens respectively were concerned about the debt burden.

Lessons learned

The latest Afrobarometer data provides lessons both for analysts of Sino-African relations and African leaders.

First, there is no monopoly or duopoly of influence in Africa. Beyond the United States and China, there is a mosaic of actors, both African and non-African, that citizens consider to have political and economic influence on their countries and their futures. These actors include the United Nations, African regional powers and Russia.

Survey findings show that although Chinese influence remains strong and positive in citizens’ eyes, it is less than it was five years ago. This decline might also be linked to perceptions of loans and financial assistance, framed by the ‘debt-trap’ narrative and allegations of Chinese asset seizures.

Once fieldwork resumes, future Afrobarometer surveys in additional countries may shed light on ways in which the pandemic and China’s ‘corona diplomacy’, and media reports on the mistreatment of African citizens in Guangzhou, have affected the hearts and minds of African populations.![]()

Folashade Soule, Senior Research Associate, University of Oxford and Edem E. Selormey, Director of Research, Centre for Democratic Development Ghana

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.