Nigerian women are at high risk of death related to pregnancy and child birth. Accurate figures are hard to come by, but the World Health Organisation estimates there are more than 800 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births in Nigeria. That’s about 100 times higher than rates in Canada or the United Kingdom.

Most maternal deaths happen in low and middle-income countries, over half of them in sub-Saharan Africa. The rate is highest among very poor women living in rural areas, and among adolescent mothers who are younger than 15. This is the situation for many women in northern Nigeria.

The standard approach to reducing maternal mortality is to encourage women to attend health facilities for antenatal care and to deliver their babies in health facilities.

But, in places with high maternal mortality and poor health services, simply advising a woman to seek routine antenatal care during pregnancy is not the answer.

The very disadvantages that increase a woman’s risk in pregnancy and child birth – like poverty or lack of education – also make her less likely to be able to attend health facilities. For those who do go to health facilities during their pregnancy, the standard of care is often poor and could be compromised further if the overstretched facilities had to cope with increased demand.

Previous studies indicate that home visits to women during pregnancy and after delivery, as part of community-based schemes, can improve the health of mothers and babies. But in most of these home visit schemes, the visitors encouraged women to visit health facilities and coverage of households was far from universal.

We undertook a trial to test the impact of universal home visits – carried out by trained female and male “home visitors” – in Bauchi, a state in northern Nigeria.

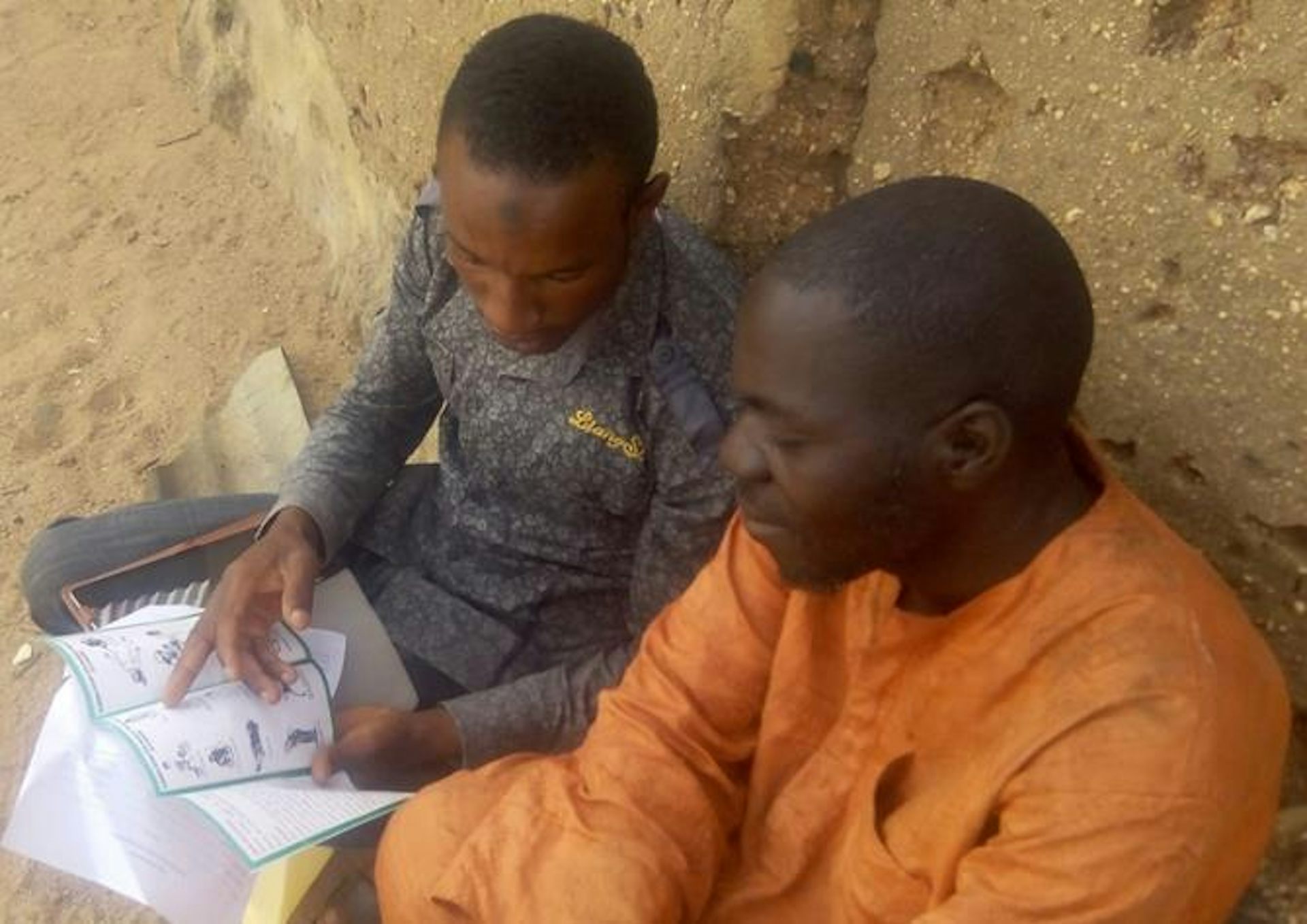

These were different from other home visits because they covered all households and pregnant women in an area, ensured that the most marginalised women were reached, and were based on local evidence about risks – like heavy work or domestic violence during pregnancy – that households themselves could tackle. They also included men. Male visitors shared the same evidence about risks with the pregnant women’s spouses.

The trial was a success. The visits improved the health of mothers without changing their use of health facilities, or the services provided by them. These are important findings for other countries with similar maternal health challenges.

Bauchi trial

A previous study in Bauchi found that women were more likely to have complications in pregnancy and childbirth if they continued heavy work throughout their pregnancy, experienced domestic violence, did not communicate with their spouse about pregnancy and child birth, and if they did not know the danger signs in pregnancy or delivery.

The Bauchi state Primary Health Care Development Agency, Federation of Muslim Women Association of Nigeria, and Community Information and Epidemiological Technologies/Participatory Research at McGill CIET/PRAM, in the department of Family Medicine, worked together to implement the Bauchi trial.

In the trial, the home visitors provided pregnant women and their spouses with information about the risk factors and what could be done to avoid them. This allowed them to reduce the risks themselves. The visitors shared information either through conversations or short video clips, in the style of locally popular soap operas.

The home visitors used android handsets to record interview responses and share the video clips. The GPS enabled handsets also allowed remote monitoring to ensure the visitors had actually visited the households.

The results

After one year of the intervention, we compared outcomes over four areas, which we call wards. Two which had received visits – totalling 1,837 women who had given birth – and two which hadn’t, with a total of 1,853 women who had recently had their babies.

Through questionnaires given to the women, we found that the home visits produced clear benefits. Women in the visited wards had less complications of pregnancy and less infections related to childbirth. The visits also reduced targeted risk factors. The women in the visited wards undertook less heavy work in pregnancy, experienced less domestic violence, and communicated better with their spouses. They were also much better informed about danger signs in pregnancy and delivery.

This all happened without an increase in use of health services in the visited wards, suggesting that the improvement in the targeted risk factors led to the improvements in maternal outcomes. The households themselves took action to reduce these risks.

All too often, special programmes implemented on a trial basis show promise, but cannot continue once a separately funded project is over. In Bauchi, officers from the Primary Health Care Development Agency, involved in implementing the home visits from the beginning, have now taken over the financial and technical management of the visits in two of the wards. The Primary Health Care Development Agency has planned and budgeted to roll out home visits in this model to the rest of the local government authorities in the state, and the research team are training government officers to run the programme.![]()

Anne Cockcroft, Associate Professor, McGill University and Neil Andersson, Professor of Family Medicine, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.