My father left my mother while she was pregnant – she gave birth when he had already left. People call me “daughter of a bitch”. They disturb and hurt me so much. They say they will chase me because I am a foreigner. I am suffering.

These are the words of Emma* – a 13-year-old girl from Beni, a city in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) near its border with Uganda. Emma’s mother Grace* was still in school when she met and became involved with a Uruguayan soldier working in DRC as a United Nations peacekeeper. When Grace got pregnant, ‘Javier’ promised his support and told her not to worry. Grace was under the impression they would get married and start a family.

Yet only a few weeks later, Javier returned to Uruguay and was never heard from again. Unable to cover the costs of pregnancy and childbirth, Grace was deeply affected by his leaving. To provide Emma with food, clothes and shelter, she was compelled to exchange sex with peacekeepers from the nearby UN base for small amounts of money or items like bread, milk and soap. She has yet to receive any support from the father or his military, and is unable to meet her daughter’s longer-term needs including her education.

In spite of the pain her abandonment has caused, Emma says she wants nothing more than for her father to return and improve her circumstances:

I feel hurt when I see UN agents passing by because other children have their fathers, but I don’t have mine. I would like to tell my father to think about me, wherever he is. He should know that I don’t have a family. If my mother dies, who will raise me?

Emma’s story is far from unique – both according to our research and the UN’s own internal reports. However, this is the first time that children of UN peacekeepers have spoken directly about the impact of abandonment on their lives and families.

Their stories corroborate our previous interviews with the mothers of peacekeeper children in Haiti. In both countries, UN personnel left impregnated women and young girls to raise children in deplorable conditions, with most receiving no financial assistance.

Our findings in DRC are based on 2,858 interviews with Congolese community members, including 60 in-depth interviews with victims of sexual misconduct who conceived children with peacekeepers, and 35 interviews with children who were born as a result. The research, which dates back to 2018, implicates UN personnel from 12 countries, the majority of whom were Tanzanian and South African. Mothers said these absent fathers held roles ranging from soldiers, officers and pilots to drivers, cooks, doctors and photographers.

According to our research, the youngest girl to have been impregnated by a UN peacekeeper was just ten years old. One in every two mothers were under the age of 18 when they conceived. In this interview, a 16-year-old mother recalls being trafficked by her family, and impregnated, at the age of ten:

I was very young – just ten years old. I realised later on that I was sold out by my aunt. The men were buying beer in the pub to share it with me. When I was drunk, they profited from unwanted sexual acts. Every morning my aunt gave me milk, bread, food and water to recover from all the lost energy. (Mother, 16)

‘Rape capital of the world’

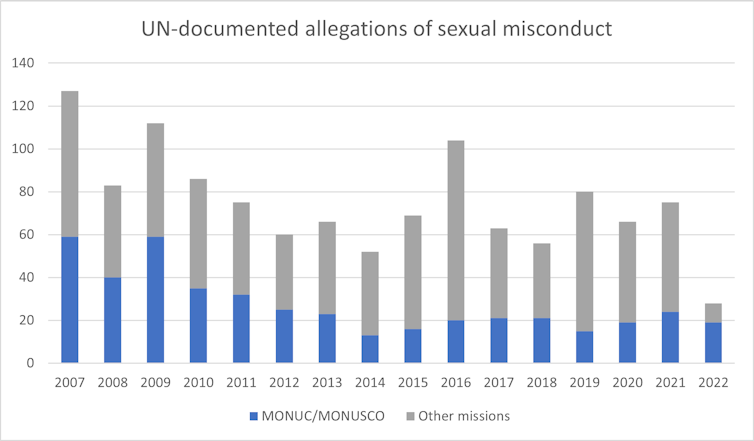

Fuelled by extremely high levels of poverty, displacement and a lack of effective judicial systems, DRC has the highest number of allegations of UN peacekeeper-perpetrated sexual exploitation and abuse of any country in the world (about a third of all such allegations since the turn of the century). Yet no systematic research on paternity claims linked to Monusco (the current UN mission in DRC, which took over from the previous mission in 2010) has existed until now.

DRC is the epitome of a war-torn country with a thriving peacekeeping sex economy. Years of colonialism, oppression by national and international regimes, power struggles and corruption have left indelible scars. Security remains highly volatile due to fighting between more than 130 armed groups. In recent weeks, there have been a number of violent protests against UN peacekeeping forces in eastern DRC, with protesters calling for the UN to withdraw from the area. In one such incident, ten people are reported to have been killed. It is against this backdrop that US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is visiting.

Sexual violence has become a defining feature of this conflicted region. Descriptions that dub DRC the “rape capital of the world” and “the worst place in the world to be a woman” reflect how the conflict-related violence has normalised rape and sexual exploitation by civilian perpetrators, humanitarian workers and UN peacekeepers.

Our interviews reveal that the majority of women and girls in DRC who had sexual relations with peacekeepers – whether willingly or forced – were living in extreme poverty. We heard a number of accounts of girls and women having been raped by one or more peacekeepers, sometimes while begging for humanitarian assistance. One participant who said she had been gang-raped by UN peacekeeper personnel at the age of 13 described heavy stigmatisation for not being able to identify her child’s father:

People started wondering where this little girl got her pregnancy from. They laughed so much at me. They said, “Look at her who has been raped, she has a white child.” Many people laughed at me. I felt so insulted, all of this hurt me so much. (Mother, 25)

While peacekeeping missions are credited with a crucial role in protecting human rights in conflict, the risk of peacekeepers exploiting or abusing those most in need of protection calls the legitimacy and morality of deploying missions into question.

More than 97,000 peacekeepers from over 120 countries currently serve in 12 peacekeeping operations around the world. Despite it being the duty of all UN personnel to protect and “do no harm”, sexual wrongdoings committed against local civilians, primarily young girls, have been reported wherever missions were put in place.

The presence of peacekeepers has repeatedly been associated with a rapid increase in sex trafficking and brothels near military bases, child prostitution, the exchange of sex for goods or food, the creation and distribution of pornographic films, growing harassment and catcalling in the streets, and the spread of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV.

A UN peacekeeping spokesperson said: “Over the past five years, we have taken action to prevent these wrongs, investigate alleged perpetrators including military contingents, and hold them accountable including through repatriation. We have strengthened our policies and protocols, and our joint investigative capacities with member states. We continue to publicly report on allegations as we receive them and on the status of these allegations in our public database. Personnel have been separated from the organisation, and no one who has been the subject of a substantiated investigation into sexual misconduct can be rehired within the system.” (See fuller response at the end of the article.)

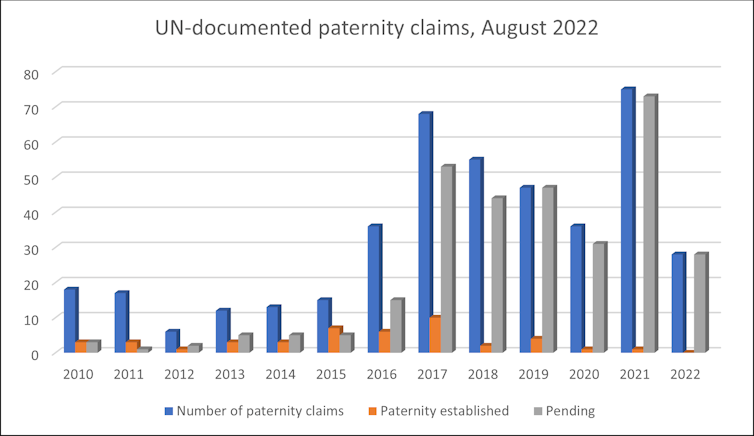

As of August 4 2022, the public database of misconduct allegations in UN field missions has logged 426 allegations of sexual misconduct that implicate peacekeepers in fathering children, dating back to 2007. Only 44 of these allegations have been substantiated, with the large majority of claims (302) remaining “pending”.

Our work in Haiti and DRC reveals that UN babies were conceived in a wide range of sexual relations, from rape and precarious “survival sex” (sex granted in return for food and protection) to dating and longer-term relationships that blur the lines between overt abuse, consent and more nuanced forms of exploitation. Most mothers described the context of their children’s conception as “transactional”, centred around the exchange of food, money, clothing or other items in return for sex:

I lived miserably before he started sending me money and solving my problems. He put me in conditions to love him. He didn’t force me. He promised to marry me and give the dowry to my family. He confirmed that he would take me to his country and wanted to have a lot of children with me. I found myself believing him, it sounded true. I didn’t see that he was telling lies. I had nothing at this point. (Mother, 23)

Voices of peacekeeper children

The earliest documentation of “peacekeeper babies” emerged during the UN presence in Timor-Leste and west Africa, where peacekeepers were said to have impregnated local women and girls, then abandoned them without any form of child support. Following these reports, further evidence emerged in relation to a number of other peacekeeping operations including in Cambodia, the Central African Republic, Haiti and DRC.

While the issue of sexual misconduct by peacekeepers has attracted significant academic and public attention, there has been much less attention paid to the children born as a result. For our DRC research project, we collected a wide range of stories from Congolese community members of all ages about the circumstances of their interactions with peacekeepers.

Participants were not prompted to talk about sexual exploitation and abuse, and could share any experiences they wanted. Their narratives were audio-recorded by trained Congolese research assistants in communities surrounding six UN bases in eastern DRC. To include children as young as six in the research, we used child-appropriate interview methods – for example, by asking them to draw their families or comment on photographs of peacekeepers and Congolese children.

Author provided

None of the peacekeeper children were in contact with their fathers when the interviews took place, and many did not know their fathers’ names or whereabouts. The majority had been told that their father left around the time of pregnancy or birth, yet few knew about the circumstances of their conception or abandonment:

Since I was born, I have never had the chance to learn anything about him apart from hearing that I have one. I have never heard his voice, not even once. (Child, 13)

All expressed frustration about the lack of material support from their fathers, indicating that even the youngest participants saw their insufficient access to resources as unjust and directly linked to their father’s absence:

I remember my mother but I know nothing about my father. This is the reason why I am always hungry. If he was living with me, I wouldn’t be hungry. (Child, 10)

Most salient was the sense of a missing purpose or direction in life. Not knowing their roots and family history left a void regarding self-worth and social conscience:

I never go to school. I have no food support and even when I do get food, I start thinking about my mother who is living abroad and my father who I have never seen. I feel meaningless in a household where I can’t be around my parents. When I think of the deep poverty I’m in, I feel much despair. (Child, 13)

Maternal networks often provided them with only limited care and attention due to their illegitimate conception and the related stigma. The deprivation of parental relationships and material possessions led some to consider themselves orphans:

My mother delivered me, she left and abandoned me when I was two months old. She dropped me off at my grandparents. When they call my mother to ask for money, she often doesn’t pick up the phone. I don’t think she considers me her child any longer. She abandoned me and my two brothers. (Child, 14)

I am like an orphan. Monusco should remember us who were left here in Kisangani. We are considered orphans. (Child, 13)

A handful of peacekeeper children gave accounts of maltreatment by their mothers that made them question their right to exist:

[My mother] never talks to me in a friendly way. She says I have no value at all, for I’m not like her other children. When she says that, I feel it’s better to take a knife, stab myself and die once and for all. I feel very upset, for I have no support from my relatives. (Child, 13)

Voices of abandoned mothers

In 2019-2020, we published the first empirical research addressing sexual exploitation and abuse-related pregnancies in Haiti. Asking 2,500 Haitians what it’s like to be a woman or girl living in communities that host peacekeepers, colleagues Sabine Lee and Susan Bartels discovered that sexual misconduct and child abandonment were a widespread concern among those interviewed. Their research brought forth the stories of mothers who were struggling to survive, let alone care for an infant after being exploited, abused or “blindsided” by peacekeepers.

In our subsequent DRC research, 1,182 (42%) of all interviews were found to be about peacekeeper-fathered children – compared with only 10% of stories in Haiti. This suggests that paternity cases may be more common in DRC, and also that in Haiti some other issues, such as peacekeepers introducing cholera to the region, were of particular concern to the women and girls interviewed.

In the early 2000s, peacekeeping in the DRC became notorious for allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse. The mass allegations associated with this mission, including the operation of sex rings and paedophile networks, implicated peacekeepers from almost all contingents and groups of personnel (military, police and civilian).

Similar to other countries where the arrival of peacekeepers coincided with a rise in child prostitution, in the DRC underage sex work rose to unprecedented levels. Although illegal, an extensive sex economy emerged with children (“kidigo usharatis” [little prostitutes]) as young as six selling sex for survival.

The shame and social stigma of sexual exploitation and abuse-related pregnancies has denied some mothers the ability to return to their families, homes and villages, preventing them from pursuing their education or careers, and having a traditional family of their own:

I am not married for I was a victim of sexual violence. I’m unoccupied, no job, no business to make money, to meet my child’s needs like powder soap, sandals and so on. My family cannot support me because they have no means, they are destitute. Currently we are starving. (Mother, 16)

Many mothers, regardless of whether or not they consented to sexual relations, were already in precarious life situations. Raising children fathered and abandoned by peacekeepers substantially weakened their economic security:

That guy from Monusco is living peacefully with his wife and children while my house is leaking and the sheets are overused. Basically, he destroyed my life when getting me pregnant. He deceived me and now my life is crammed with suffering [and] impending hardships. (Mother, 36)

Having to cover the expenses of maternity and childcare, some found themselves in a downward spiral of further social rejection as extreme poverty led them to re-engage in sex-work to meet their child’s basic needs. Some mothers reported having several children from different peacekeepers:

I didn’t care what was right or wrong. I was willing to do whatever in return for food. My worries were to find clothes for the child. I was living far from my family, I stopped going to school and willingly became a prostitute. Men gave me money which helped a lot. I gave birth to the first child, then the second. (Mother, 21)

Due to local customs of sexual exclusivity, bride value is dependent on virginity and girls who are known to have had sex before marriage struggle to maintain their societal status. Mothers of peacekeeper children faced prejudice for being perceived as promiscuous, HIV positive and disrespecting traditional gender roles – often regardless of their age or whether the sex was consensual:

Because of this child, my life is dark. No man will ever intend to marry me. They call me a Beninese’s wife. My reputation is ruined. When people learn that you were once friends with a guy from Monusco, they start despising you and talking ill of you. It is not easy to find another man-friend if you have been deceived by one of them. (Mother, 36)

Many mothers reported feeling responsible for their children’s difficult socio-economic circumstances, like they were passing their own hardship down to their children:

People in the community gossip much about my life. Some say that I broke my marriage promise because of a foreigner who is the reason I am now a desperately poor woman … I sometimes wonder whether I should kill myself or my child, but I guess I just need to hold on and bear the consequences of my decisions. If his father returns, we can get our dignity back. (Mother, 43)

Observing peacekeeper children’s social and economic deprivation led to additional guilt in mothers who blamed themselves for being a neglectful parent:

The child asks every day, who is my father? Where does he live? What’s his nationality? All this leads to remorseful life, a child should know. She asks, how shall I see him? And then answers for herself, there is no way to see him. The neighbours constantly make fun of her saying that she is the ‘daughter of a white’. My friends were even bringing different kinds of poison in order to kill her. Because of this she only stays here in the compound, she is ashamed. (Mother, age unknown)

Author provided

Desire to be reunited

When asked to draw their family, the majority of peacekeeper children drew a nuclear family with an underlying structure that did not match their family’s actual situation. Several peacekeeper children were explicit about the drawing being an expression of their desire to be reunited with their fathers:

The drawing means that I want to have the father and mother in our house. (Child, 7)

Participants of all ages discussed the possibility of searching for their fathers to make this imagined family a reality. Almost all anticipated that financial contributions would result from reconciling with their fathers:

I want him to come rescue me from poverty. I would show him that I have no clothes, no food, no body lotion. I would ask him to give me money for school fees. With him present, I would be proud to tell people that I have a father. Other children who are living with their parents must be living well, I think. (Child, 13)

The identities of peacekeeper children were typically well known, and even the youngest interviewees felt judgement from their communities due to the circumstances of their conception. Stigma was manifested in a range of experiences, from teasing and bullying to overt discrimination, abuse and neglect:

Some people say I am different because my father left when I was a baby. Some are amazed to see I am still alive. When I hear people gossiping about me and my father – a father I haven’t even seen – it hurts my heart so much, I start weeping right away. (Child, 14)

These comments support the representation of peacekeeper children as an “out-group” in their communities. Conceived by foreigners, these children carry stigma due to their different looks and inter-ethnic background. They reported being humiliated or ridiculed on the grounds of not being Congolese, being “white” or “foreign”, or otherwise singled out for their ethnic heritage. Some of the most recurrent insults directed towards peacekeeper children were “daughter/son of a bitch”, “bastard” or “illegitimate”.

The child is discriminated everywhere he goes. He is insulted as a ‘son of a bitch’. They say he isn’t worth it to be alive. (Mother, 20)

Barriers to justice

The standard period of duty for UN peacekeepers is six to nine months, making it highly improbable that peacekeepers are in the host state when their children are born. Bound by agreements between the UN and member states, the UN’s role in advancing paternity claims is limited to coordinating and facilitating them. Instead of offering compensation through the UN, assistance protocols refer accountability to assailants and their home countries, emphasising the individual liability of perpetrators. However, member states are often unwilling or unable to cooperate, letting many allegations go unresolved.

To date, no information concerning successful child support has been made public, raising the question of whether any mothers are regularly receiving support. While a landmark legal decision was reached in Haitian courts in 2021 – ordering a Uruguayan peacekeeper to pay support for a child he fathered and abandoned in 2011 – a clear mechanism for enforcing this ruling through the national legal system of the peacekeeper’s home state has (to my knowledge) not yet been established.

The UN’s zero-tolerance policy bans almost all sexual relations between peacekeepers and local civilians, deeming them exploitative or abuse due to the context (conflict, poverty, displacement) in which they occur. Yet our data shows this blanket ban on sexual relations is ineffective and that there are no accessible and worthwhile complaint pathways for victims. The lack of prosecution and effective legal responses to offences – depicted by our research in both Haiti and the DRC – demonstrates that peacekeepers can not only get away with sexual misconduct, they can father and abandon children without facing consequences.

Of the 26 mothers we interviewed who had contacted UN peacekeeping authorities in DRC to report a paternity case, the majority indicated their complaint had been ignored or rejected. While a fifth described undergoing an initial investigation or legal case, no interviewee had been awarded legal compensation.

I went to Monusco when the child was four years old. I asked them to help me be in touch with the father as I was burdened with the child’s responsibilities and charges all by myself. They asked me to come back after one month to get some food. They gave me rice, beans, cooking oil; the next month they did likewise. In the third year, they chased me away and asked me to open a case somewhere … I understood that there was no support and decided to stay at home. (Mother, 28)

Some participants detailed that UN officials violated their right to information about how to take legal action, reinforcing the widely shared notion that the UN had no interest in holding peacekeepers accountable for fathering children:

I tried to speak to Monusco officials and requested that they look for the father in his country, but my effort was unsuccessful. I went to the place where women who are left with children go to expose their problem to a woman working for the UN. When I went there, I saw no reaction. In fact, they didn’t do anything. It is hard to understand (interviewee cries). (Mother, age unknown)

Mothers who gave accounts of an initial investigation often described poor follow-up and mismanagement of their cases, lengthy delays and non-compliance with promised next steps. In some instances, illegal processes and corruption were considered to have led to victims not being treated according to UN guidance. One mother described the doctor who conducted her child’s DNA test having been bribed. In several instances, allegations of sexual misconduct and childbirth were said to have been swept under the carpet:

The officials at Monusco did not answer, they did not do anything – as if they were silently backing up the actions of this man. Luckily, the superior of my husband was relocated, and they brought in a new chief to the mission. When my parents presented the case to him, he pressed my husband to pay charges. We found out the former gentleman was corrupt. (Mother, age unknown)

And when credible evidence was found that substantiated an allegation, the repatriation of implicated peacekeepers interfered with participants’ chances of being supported, since it removed the alleged offender from Congolese jurisdiction and thus prosecution in the host state. In one example, a woman reported a Bangladeshi peacekeeper to his superiors. she told us:

I explained to them how their soldier had abused me and got me pregnant without providing any care … When I came back to present my arguments, they revealed that he was sent back to South Africa because I had reported him. I learned that he was reshuffled to South Africa without listening to what I had to say. I decided it was better to drop the matter since it was already entangled with discrimination and scorn. (Mother, 35)

A heavy burden

Both our research and the UN’s internal reports demonstrate that the group of children who have been fathered and abandoned by peacekeepers in DRC is significant and will continue to grow. The UN could and should play an important role in facilitating communication with fathers and educating peacekeeper children about their rights.

Our work in DRC, for the first time, has provided peacekeeper children with the opportunity to tell their stories and help shape responses to their unique situation. Currently, many of these children are excluded from participating in society and are disproportionally disadvantaged.

Peacekeepers, who are expected to act more ethically than local warring factions, lose their legitimacy as facilitators of peace when they engage in sexual misconduct and child abandonment. The betrayal of the host state’s trust is compounded when the UN fails to care for the victims and their children.

Academic researchers have highlighted the benefits of mandatory DNA testing for all peacekeeping personnel prior to their deployment, to provide evidence in any future cases of alleged rape or paternity claims. However, in all but one member state (see recent developments in South Africa) testing has not been made mandatory and even in instances of positive tests, obtaining legal recognition of the identity of the father and a settlement for support is anything but straightforward.

The UN has, though, taken some important steps towards better supporting mothers and children in recent years. This includes the establishment of the Office of the Victims’ Rights Advocate and the Trust Fund for Victims, which aims to provide specialised services to victims, such as educational support for children born of exploitation or abuse.

While these welcome advances are starting to show some effect, the UN acknowledges major gaps with regard to legal reparations – especially paternity and child support that deny children such as Emma a happy childhood, and might perpetuate intergenerational cycles of poverty, stigma and abuse. Resolutions and disciplinary measures may be becoming more comprehensive, but allegations continue to be levelled and the damage left behind remains unrepaired:

We are carrying a heavy burden raising abandoned children without any means. The other mothers – there are so many – are also sitting on a mountain of problems. They do nothing and are in very critical situations. We have all become like street children. We really do need some help. (Mother, 35)

*All names have been changed to protect participants’ anonymity.

UN response

The UN acknowledged that “despite clear gains in the UN’s response to incidents of sexual exploitation and abuse”, allegations implicating UN personnel continue to emerge, including in peace operations. It said that among these were historical allegations, which its staff on the ground were working to uncover. A spokesperson said it was disturbing that cases continued to surface but that “over the past five years, we have taken action to prevent these wrongs, investigate alleged perpetrators including military contingents, and hold them accountable including through repatriation.

“We have strengthened our policies and protocols, and our joint investigative capacities with member states. We continue to publicly report on allegations as we receive them and on the status of these allegations in our public database. Personnel have been separated from the organisation, and no one who has been the subject of a substantiated investigation into sexual misconduct can be rehired within the system.”

The UN said that the first victims’ rights advocate was appointed five years ago to lead efforts promoting the rights and dignity of victims alongside dedicated advocates on the ground. “They ensure victims receive medical, psychosocial and legal support, support them during UN and member state investigations, and support them to pursue paternity and child support claims.” It said that “while the UN does not compensate the victims financially, projects financed by the Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse have allowed them to upgrade their skills so they can engage in income generating activities, enabling them to rebuild their lives … We know that much more must be done and we continue to step up our efforts”.

“The secretary-general’s most recent report on special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse acknowledges the disturbing fact that many paternity/child support claims relating to peacekeeping personnel remain unresolved. Their resolution is the joint responsibility of the UN and member states to ensure that the fathers’ parental obligations can be realised. These are complex cases, usually involving several jurisdictions with differing legal frameworks. The UN is committed to working with member states to find a solution to this challenge.”

It said the UN secretary-general “urges troop and police-contributing countries with paternity claims pending for six months or more to take clear steps to facilitate their resolution, including by addressing substantive and procedural legal obstacles. He has also asked the victims’ rights advocate to facilitate the provision of basic assistance and support, including food, schooling and medical and psychosocial care, to the mothers and children. He has instructed the victims’ rights advocate, in collaboration with other UN entities, to develop a reinvigorated strategy to address these claims.”

Kirstin Wagner, Research Fellow, Psychology, University of Birmingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.