The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is a vast country rich in natural resources including the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, and substantial quantities of diamonds, gold and copper.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is a vast country rich in natural resources including the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, and substantial quantities of diamonds, gold and copper.

It also has the hydroelectric capacity to light up all of Africa with enough left over to power Europe. And, it hosts the second-largest rain forest in the world, a forest that spans six countries across Central Africa.

In 1960, the republic gained independence from the Belgian government.

By 1965, it was the second most industrialised country in Africa after South Africa, boasting flourishing agricultural and mining sectors.

Despite such a good start, the DRC has become a theatre of a complex and protracted humanitarian crisis. At least 1.6 million people have been internally displaced, 90% of whom have left their homes due to armed attacks.

In 2016, more than 920,000 Congolese were internally displaced by conflict. This compares with 824,000 in Syria and 659,000 in Iraq.

On top of this, the DRC is rated sixth on the list of countries that generate the most refugees.

The situation is really bad according to, Ulrika Blom, the Norwegian Refugee Council’s Country Director:

Even Syria or Yemen’s brutal wars did not match the number of new people on the move in DRC last year.

Since December 2016, ethnic violence has spread and worsened in the wake of President Joseph Kabila’s refusal to step down after serving two consecutive terms.

The political insecurity brought on by his reluctance to call a general election has aggravated long-standing ethnic tensions and triggered clashes between armed groups particularly in the provinces of North and South Kivu to the east of the DRC.

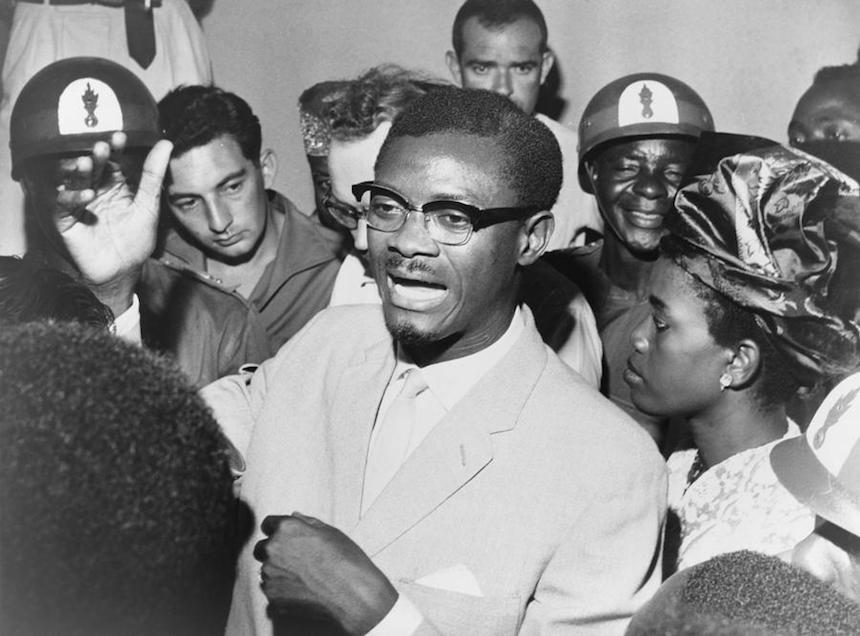

The country is moving further and further away from the vision of Patrice Lumumba, one of its founding luminaries, a man who strongly defended human rights. What can it learn from him?

Lumumba’s vision in tatters

Lumumba declared in 1958:

We wish to see a modern democratic state established in our country, which will grant its citizens freedom, justice, social peace, tolerance, well-being, and equality, with no discrimination whatsoever.

He believed that an intelligent, dynamic and constructive opposition was necessary to counterbalance the political and administrative actions of the government in power. He spoke against the balkanization of the country, then known as Zaire, and was strongly opposed to a devolved system of government.

But contrary to his vision, the DRC’s political leadership has plundered the country’s resources, subduing tribal chieftains in the process. In the end, regional leaders were denied a chance to partake in the bounty and they revolted.

This can be seen from the fact that Lumumba’s vision for a united country is being tested as pockets of ethnic violence flare up in the regions, particularly in North Kivu, which remains extremely volatile.

Since the end of 2015 and all through 2016, violence meted out by Mai Mai militias, and rebel groups including the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, and the Allied Democratic Forces of Uganda, have forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes.

In 2016, Human Rights Watch recorded the assassinations of more than 700 civilians in Beni territory, killings that had taken place over two years.

It remains unclear who carried out the attacks. The Congolese government blamed an armed group that had been active in the area, while independent sources implicated Congolese army officers in some of the attacks.

While hundreds of thousands have been internally displaced, scores of others are fleeing the country. By mid-2016, 535 866 Congolese had taken refuge abroad. A total of 78 090 others were seeking asylum and are still waiting to be granted refugee status.

The UNHCR and its implementing partners have launched an appeal for $65 million to help the growing number of refugees arriving in Angola from the DRC’s Kasai region, which has been engulfed in violence since 2016.

The violence was set off by Kamwina Nsapu (“black ant”) the leader of the Bajila Kasanja clan, who led an insurrection against the central government before being gunned down. As a result of the insurrection, 400 000 children are at risk of severe and acute malnutrition.

Time to act

Back in 1960, speaking at the All African Conference in Leopoldville (Kinshasa), Lumumba set out a vision for the country that included:

- ending the suppression of free thought and seeing to it that all citizens enjoyed freedoms laid down in the Declaration of the Rights of Man

- doing away with discrimination

- bringing peace to the country, not by using rifles and bayonets, but through good will.

To achieve this, he said, the country could

count not only on our tremendous strength and our immense riches, but also on the assistance of many foreign countries, whose collaboration we will always accept if it is sincere and does not seek to force any policy of any sort whatsoever on us.

![]() His vision is as prescient today as it was then. It’s time the DRC put Lumumba’s words into practice.

His vision is as prescient today as it was then. It’s time the DRC put Lumumba’s words into practice.

Cristiano D’Orsi, Research Fellow and Lecturer at the South African Research Chair in International Law (SARCIL), University of Johannesburg

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.