Language is a crucial element of any criminal justice system. Forensic linguist David Wright has written that people find themselves in the judicial system’s linguistic webs at every step of the legal process.

There is a substantial amount of South African legislation that confirms an individual’s right to speak and be spoken to in the language they fully understand, particularly during court proceedings. This right is even enshrined in Section 35(3)(k) of the Constitution, which confers the right to a fair trial. Courts are also obliged, during criminal proceedings, to provide a competent interpreter if the accused does not understand the language in which court proceedings are conducted.

Despite all this, South Africa’s Chief Justice has decreed English to be the only language of record in the country’s courts. The directive is an attempt to redress the practices of the past and transform the justice system. According to the Chief Justice, making English the only language of record will ensure that all judges are able to follow proceedings and produce judgments that are accessible for all parties on appeal and review.

Different languages may still be spoken in courts. But a study we conducted found that lawyers are inclined to speak and write to their clients in English.

This, coupled with the fact that the Chief Justice’s directive means written court records must be kept in English, means that most South Africans cannot access justice in their own languages. After all, only 8.1% of South Africans speak English at home. It is only the country’s sixth most common home language. Statistically, then, there’s a 91.9% chance that a South African will be at a disadvantage during a court case because they cannot properly follow the proceedings, documents and records.

What the research says

A language survey conducted by Legal Aid South Africa in 2016 showed that only 27% of state aid applicants in criminal cases speak, read and write English at a satisfactory level. An average of 54.2% of applicants in criminal cases were found to have little or no knowledge of English as a medium of communication.

Legal Aid South Africa provides legal aid to those who cannot afford their own legal representation. Their clients are already vulnerable, economically; their inability to communicate fluently in English disadvantages them further.

Our new research suggests another linguistic problem in the system: legal practitioners don’t consider how their clients might be struggling with the language of legal proceedings regulated by the language of record policy.

This is a further layer of discrimination in the justice system. And it means that these clients may not get the best possible access to justice.

We conducted our study among 100 legal practitioners registered with the respective law societies in South Africa. Some work in private practice; others are government employees. All nine of South Africa’s provinces – and thus different language communities – were represented.

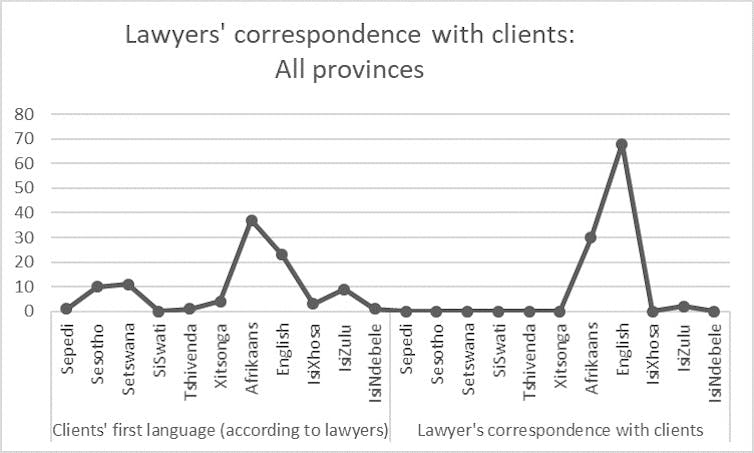

We found that most of these lawyers believed most of their clients spoke English or Afrikaans as home languages. This is surprising, given the fact that only 20.3% of South African citizens speak both Afrikaans and English at home and 26.3% speak Afrikaans and English outside their home. Legal Aid South Africa’s study indicated that most Legal Aid clients spoke isiZulu, isiXhosa or Afrikaans as their home languages.

The data from our study also showed that even when lawyers knew their clients didn’t speak English as a home language they continued to communicate, in writing and orally, with those clients in English. This happened even when the lawyers themselves spoke their clients’ home language and would be able to communicate properly with them in this language.

The primary reason the lawyers gave for this was that court proceedings and the record were conducted in English only. Interpreters may have been present, but only their English statements were placed on record. English was the status quo, lawyers said, and sticking to it was easier.

The nonchalant way in which legal practitioners deal with language is alarming. It’s also troubling that they recognise language as being critical to accessing justice – but they mostly blame the country’s court interpreters for language difficulties during court proceedings. The blame is often placed on poor quality interpretation underpinned by a shortage of interpreters and a lack of specialist legal and linguistic training for interpreters. They say interpreters are not sufficiently qualified.

The data showed that the lawyers have no faith in the court interpretation system and because of that, they conduct court proceedings in English. They’re only really concerned with the judge understanding proceedings in English, and the interpreter interpreting back into English what the witness has said.

Potential solutions

We can suggest a few ways to change the South African legal system so that people’s rights are served better.

Awareness campaigns must be launched to highlight the important role of language in access to justice. A variety of government departments, the judiciary, universities and the Pan South African Language Board should all be involved in this.

Section 6 of the Constitution states that the nine official African languages must be promoted and elevated to ensure parity of esteem alongside English and Afrikaans. For this to happen in courts, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development’s language policy should be amended to give clear directives for how African languages can be implemented incrementally in courts and be used as languages of record.

Human resources matter, too. Judges should be placed in courts where they understand the language of the community. This would reduce the reliance on interpreting services and improve access to justice through language.![]()

Annelise de Vries, Researcher & PhD Candidate, University of Johannesburg; Russell H. Kaschula, Professor of African Language Studies, Rhodes University, and Zakeera Docrat, Postdoctoral research fellow (Forensic Linguistics/ Language and Law), Rhodes University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.