One of the planet’s – and Africa’s – deepest prejudices is being demolished by the way countries handle COVID-19.

For as long as any of us remember, everyone “knew” that “First World” countries – in effect, Western Europe and North America – were much better at providing their citizens with a good life than the poor and incapable states of the “Third World”. “First World” has become shorthand for competence, sophistication and the highest political and economic standards.

So deep-rooted is this that even critics of the “First World” usually accept it. They might argue that it became that way by exploiting the rest of the world or that it is not morally or culturally superior. But they never question that it knows how to offer (some) people a better material life. Africans and others in the “Third World” often aspire to become like the “First World” – and to live in it, because that means living better.

So we should have expected the state-of-the-art health systems of the “First World”, spurred on by their aware and empowered citizens, to handle COVID-19 with relative ease, leaving the rest of the planet to endure the horror of buckling health systems and mass graves.

We have seen precisely the opposite.

Fatal errors

“First World” is often code for countries run by Europeans or people of European descent; some of the worst health performers on the globe in recent weeks have been “First World”. For Anglophone Africans, it is doubly interesting that two of the greatest failures in handling COVID-19 are the former coloniser, Britain, and the English-speaking superpower, the United States of America.

Both countries’ national governments have made just about every possible mistake in tackling COVID-19.

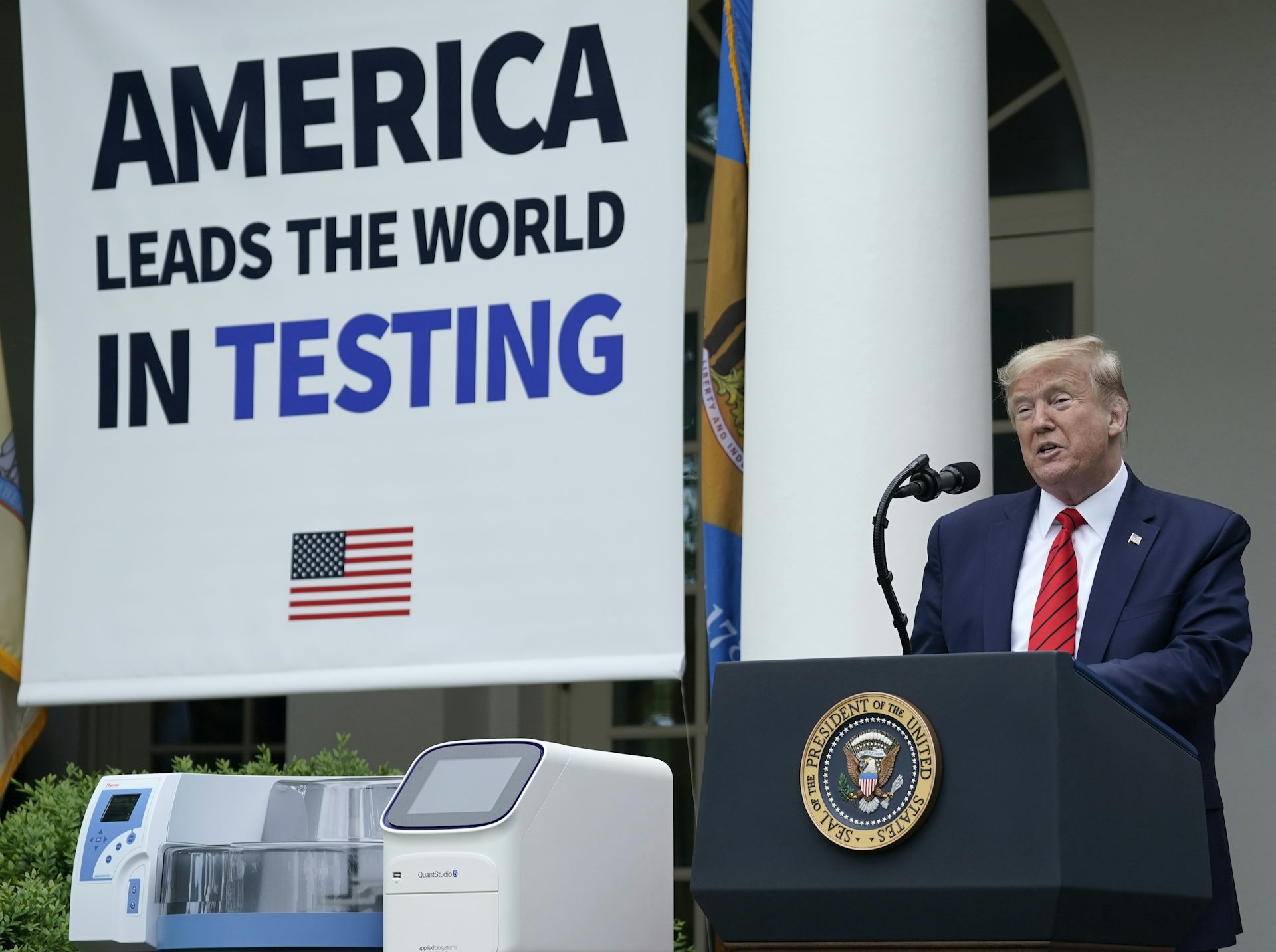

They ignored the threat. When they were forced to act, they sent mixed signals to citizens which encouraged many to act in ways which spread the infection. Neither did anything like the testing needed to control the virus. Both failed to equip their hospitals and health workers with the equipment they needed, triggering many avoidable deaths.

The failure was political. The US is the only rich country with no national health system. An attempt by former president Barack Obama to extend affordable care was watered down by right-wing resistance, then further gutted by the current president and his party. Britain’s much-loved National Health Service has been weakened by spending cuts. Both governments failed to fight the virus in time because they had other priorities.

And yet, in Britain, the government’s popularity ratings are sky high and it is expected to win the next election comfortably. The US president is behind in the polls but the contest is close enough to make his re-election a real possibility. Can there be anything more typically “Third World” than citizens supporting a government whose actions cost thousands of lives?

Western European countries such as Spain, Italy and Africa’s other wholesale coloniser, France, also battled to contain the virus. Some European countries have coped reasonably well, as have some run by the descendants of Europeans such as New Zealand and Australia. But the star performers are not in the historical “First World”.

Effective responses

The most effective response was probably South Korea’s, followed by other East Asian states and territories. This is partly because they are used to dealing with coronavirus outbreaks. But it is also because they learned from experience: South Korea’s success is due to very effective testing and tracing of infected people. Whatever the reason, it is East Asia, not “the West”, which has done what the “First World” is expected to do.

Some would reply that East Asia is now “First World”. So, it is still superior; it has simply changed its address. This is debatable. But, even if it is accepted, some places have contained the virus in distinctly “Third World” conditions.

Kerala was the first Indian state to encounter the virus but has kept deaths down to three. It had largely curbed COVID-19 but is now dealing with nearly 200 cases, all people arriving from other parts of India. Judging by its record so far, it will contain this outbreak too.

Kerala, too, has learnt from handling previous epidemics. It also has a strong health system. But one of its key tools is citizen participation: it has worked with neighbourhood watches and citizen volunteers to track the contacts of infected people. Students were recruited to build kiosks at which citizens were tested. Kerala also had the capacity to ensure that all children entitled to school meals received them after schools were closed: non-governmental organisations were mostly responsible, emphasising the partnership between the government and citizens.

Kerala’s performance is not a fluke: it has, for years, produced better health outcomes and literacy rates than the rest of India.

Nor has Africa’s response to the virus confirmed prejudices. When COVID-19 began spreading, it became almost routine for reports, commentaries – and Melinda Gates, who, with her husband Bill, heads the couple’s development foundation – to predict that Africa would be engulfed in death as the virus ripped through its weak health systems. This is, after all, what is meant to happen in the “Third World” and particularly in Africa, which is always considered the least capable continent on the planet.

So far, it has not happened. It still might but, even if it does, some countries are coping better than the dire predictions claimed (and, perhaps, better than the “First World”). One stand-out is Senegal, which has devised a cheap test for the virus and has used 3-D printing to produce ventilators at a fraction of the going price. Africa, too, has experienced recent outbreaks, notably of Ebola, and seems to have learned valuable lessons from them.

Inspiring

The “First World” is still far richer than the rest of the planet and may well remain so. So its politicians, academics and journalists will probably still believe they are better than the rest.

But the COVID-19 experience may just trigger new thinking in the “Third World”. The most basic function of a government is to protect the safety of its citizens. Ensuring that people remain healthy is at least as important a guarantee of safety as protecting them from violence.

Reasonable people would surely much rather be living in Kerala or Senegal (or East Asia) right now than in Europe and North America, raising obvious questions about who really does offer a better life.

That should inspire Africans and others in the “Third World” to ask themselves whether it makes sense to want to be America, Britain or France. COVID-19 has made a strong argument for wanting to be East Asia – or, given Africa’s circumstances, Kerala.![]()

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.