When news broke that soldiers had mutinied in Burkina Faso, it was hardly surprising. Burkina Faso’s history has been plagued by both army mutinies and military coups d’état.

Earlier this year an attempt was foiled. Even then it was clear that it was possibly only a matter of time before another was made.

And recent history in the region served a strong signal too. Over the last two years there have been coups in nearby Guinea and Chad , multiple coups in Mali , and a failed attempt last year in neighbouring Niger.

As far as coup attempts go, Burkina Faso was the missing piece in coup puzzle stretching from from the Atlantic to the Red Sea.

That this region would be plagued by coups might strike some as unsurprising. The average rating of this stretch of countries in the Fragile States Index is 98, easily worse than recent coup cases like Myanmar, a so-called “failed state” such as Libya and placing the region far closer to bottom-ranked Yemen and Syria than countries like Senegal or Ghana.

Relative to other regions, the Sahel faces extraordinary challenges. It’s nevertheless surprising that there has been such a high number of coups in such a short period of time.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently lamented what he called an “epidemic of coups,” while acknowledging “effective deterrence is not in place.” In Guterres’s view, responses to coups have been handcuffed as potential anti-coup enforcers struggle with their own problems during the pandemic. The result, he argues, is

an environment in which some military leaders feel that they have total impunity, they can do whatever they want because nothing will happen to them.

Decline in counterveiling forces against coups

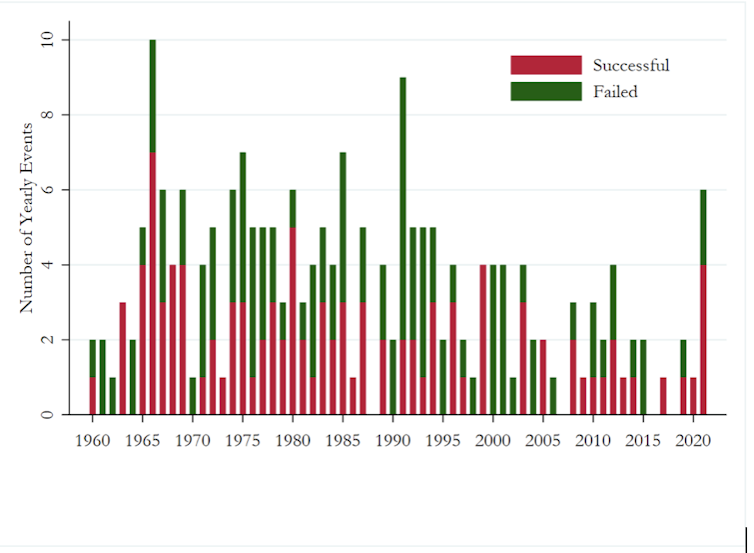

By various accounts , post-colonial Africa has seen over 200 coup attempts, with roughly half seeing the leader successfully removed. And though recent years have hardly seen the phenomenon completely retreat as a threat, the practice had greatly declined.

Not since 1999 had so many successful coups occurred in a calendar year and not since 1980 had there been a year with more successful coups. Though 2021 appeared exceptional, the coup in Burkina Faso could suggest 2021 was no fluke.

Though many of these countries share fragile domestic political environments, many observers have commented on the weakening of a presumed anti-coup norm that was argued to be at least partially responsible for the decline in coups.

In the past, post-coup regimes saw suspensions remain in place until prominent coupists fully retreated from power. In the case of Madagascar, it was nearly five years. Such responses have given way to seeing membership restored and sanctions dropped so long as coupists participate in an election. Not only are former coup leaders such as Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and and Mohammed Ould Abdel Aziz welcomed back, they were even chosen to serve as the organization’s chairperson.

More recently, the organisation has simply chosen to ignore coups altogether in 2017 Zimbabwe and 2021 Chad.

Nor has the behaviour of world powers acted as a deterrent. China, for example, has taken a “without conditions” approach to its loans and assistance, viewing the occasional coup as little more than “the cost of doing business” in the region. Though the US has regularly suspended assistance after coups, as with the AU, they have been happy to end those suspensions so long as the coupists test the vote.

Sudan’s coup leaders, for example, were perhaps anticipating an Egypt-like progression in which any suspension of its $700 million aid package would be temporary. In the case of military aid, even if the US or other Western actors response harshly, alternatives are increasingly willing to step in.

Put simply, the lesson learned from coups is that any costs are short-lived.

In addition to changing international dynamics, there seems to be a change in attitude on the part of people living in countries experiencing coups. Citizens in places like in Burkina Faso have in the past rallied to thwart coups. More recently, peoples’ willingness to tolerate coups seems to be increasing.

Neighbouring Mali has seen its people protest against ECOWAS’s post-coup sanctions, while a recent polling effort suggests over 90% of respondents in Bamako support military rule. The most recent data from Afrobarometer – an independent research network that measures public attitudes on economic, political, and social matters in Africa – pegged nationwide support for military rule in Mali to be at around 31%.

By comparison, 50% Burkinabe respondents approved or strongly approved of military rule in the same sample. This is up 10% from a decade earlier.

Politics by the gun

Tomorrow’s would-be coupists are emboldened by every case that lacks robust responses – from within and without.

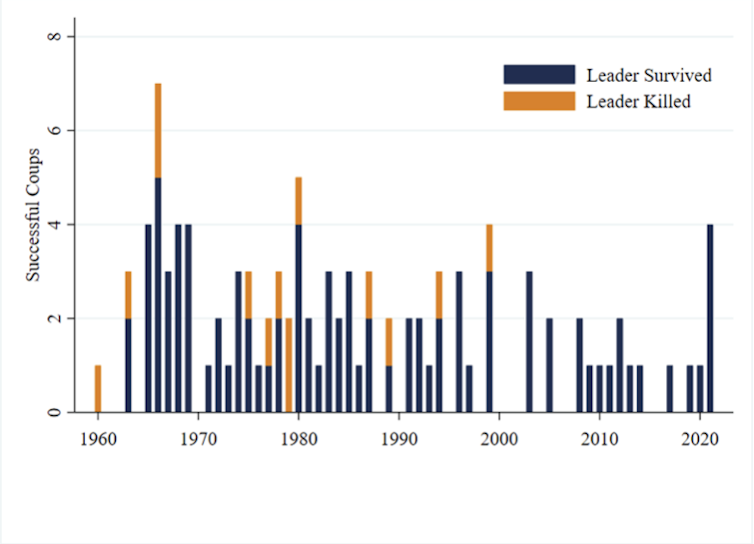

The normalisation of coups does not simply mean an increase in “irregular” transfers of power. It means an increased acceptance of politics by the gun. The reported attempt on President Roch Kabore’s life could be a further indication of a throwback to an earlier coup era. An underappreciated trend accompanying the decline of coups is that though they still occasionally occur, they have become far less likely to be accompanied by political assassination.

At the time President Ibrahim Bare Mainassara was killed in an April 1999 coup in Niger, Africa had seen 14 of 82 ousted leaders killed during the attempt or as a direct consequence of it.

Following the April 1999 coup in Niger, a period which coincided with the continent’s establishment of an anti-coup norm, no leaders have been killed in the last 24 successful coups. Admittedly, this streak is at least in part due to a quirk of definitions, as the killing of Guinea-Bissauan President João Bernardo Vieira is generally considered to be a mere “assassination.”

Compared to earlier eras, however, coups in the last 20 years have been comparatively tamer. It’s important to note that violence is a tool whose use all coup leaders accept. Nevertheless, the level of violence associated with them has dramatically decreased over time. This is not a coincidence . Leaders such as Sylvanus Olympioin 1963 , and Thomas Sankara in 1987 were not killed by accident. These were murder victims whose deaths were meant to facilitate a coup’s success and to eliminate a future political threat.

The normalisation of armies as political actors inevitably means the use of the military toolkit in politics. With growing support for army intervention and less interest in preventing coups these are trying times for those wary of returning trading the ballot box for bullets.![]()

Jonathan Powell, Associate professor, University of Central Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.