The scale and frequency of attacks launched by the terrorist group’s East African affiliate are increasing.

Editor’s Note: Although the core of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria has been hit hard, it still has several branches that are prospering. Charlie Winter of ExTrac describes how the organization’s branch in Mozambique is getting stronger, warning that the imminent departure of the South African Development Community military mission makes it likely that the Islamic State threat to Mozambique and its neighbors will grow. – Daniel Byman

On May 10, the Islamic State’s Mozambican affiliate executed one of its most ambitious attacks in recent years, targeting the town of Macomia in northern Cabo Delgado. This coordinated dawn assault involved dozens of militants attacking from multiple directions, highlighting a marked shift in the group’s tactics from hit-and-run raids to more organized, multipronged operations.

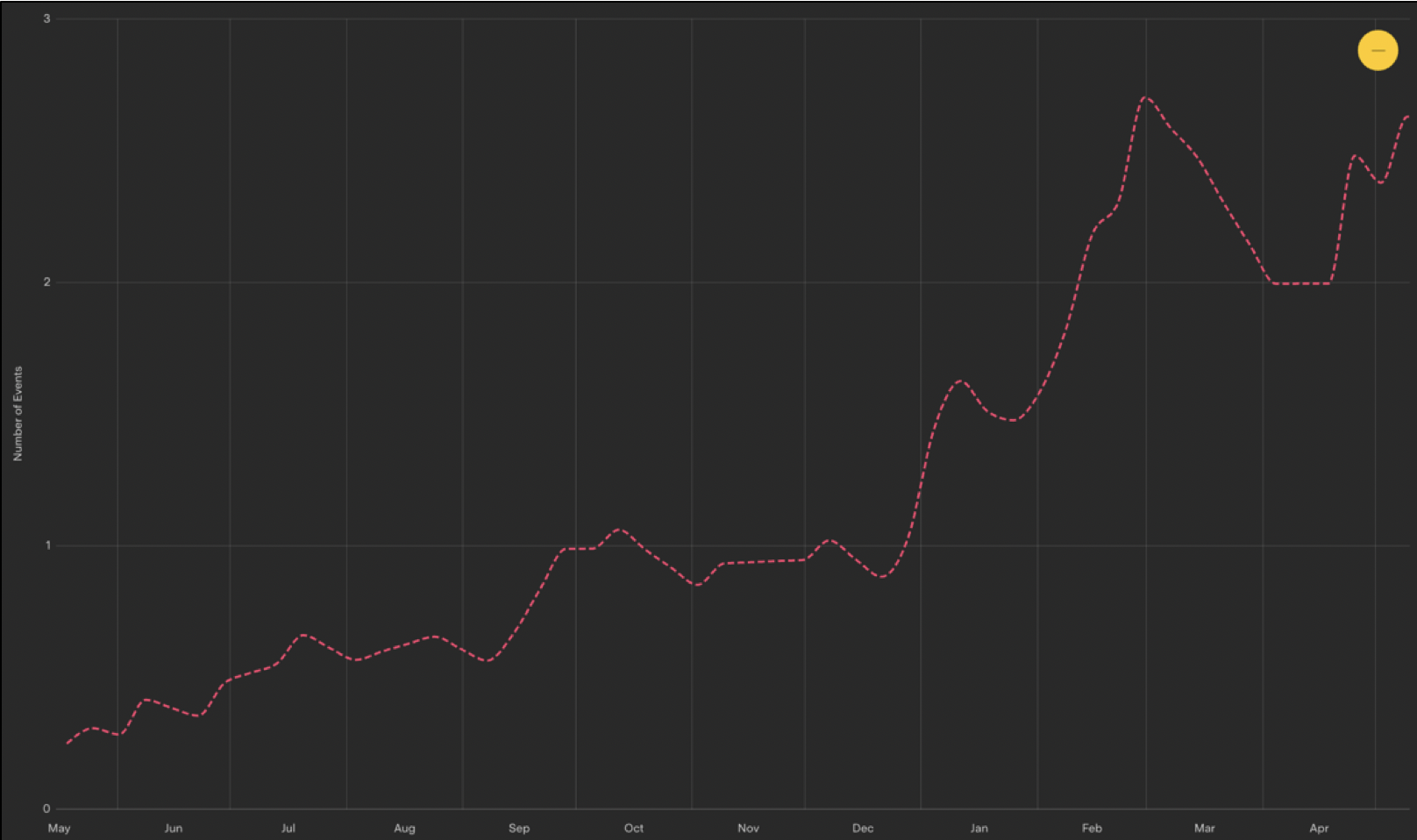

Longitudinal analysis of Islamic State-Mozambique (IS-M) attack and communications data evidences a significant transformation in its operations in recent months. While the organization’s activities were characterized by opportunism through much of 2023, it is evolving toward more complex assaults and expanded recruitment efforts.

It is no coincidence that this shift correlates closely with the winding down of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) military mission, which has been active in Mozambique since July 2021 and is scheduled to end in July 2024. The mission, dubbed the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM), consists of 1,900 personnel from eight countries, along with dozens of armored vehicles, a transport plane, and even a naval strike craft. While relatively modest in size, its impact has been significant, with SAMIM forces providing extensive intelligence, tactical, and material support to their Mozambican counterparts. About 1,500 SAMIM troops are from the South African National Defense Force and, until April of this year, most of those 1,500 soldiers had been deployed at the Mihluri base on the outskirts of Macomia.

The drawdown of SADC forces seems to have created a strategic vacuum that IS-M is now exploiting to escalate its activities in the region.

The Macomia Assault

The attack on Macomia was reportedly led by Abu Fasade Ali Alide, who is believed to have previously commanded the March 2024 assault on Quissanga, another district capital in Cabo Delgado.

Initial reports suggest that the Macomia raid involved at least 100 militants attacking from multiple directions, with fighting concentrated in the areas of Xinavane, Bangala, and Nanga. Although the Mozambican government initially claimed to have repelled the assault, independent verification was lacking and local sources indicated that IS-M militants remained in the town until May 11.

The strategic implications of the attack on Macomia are significant. For IS-M, this was not just a tactical operation but a demonstration of its ability to execute coordinated assaults that don’t just challenge the capabilities of local security forces, but utterly undermine them.

Escalating Violence and Strategic Ambitions

The recent escalation in IS-M’s activities can be attributed to several key factors. The impending withdrawal of SADC forces has undoubtedly emboldened the group, providing it with opportunities to expand its territorial control and influence.

As the chart shows, in the first quarter of 2024 alone, IS-M operations occurred at more than three times the rate that they occurred in the same period last year, intensifying in both frequency and complexity.

This evolution in tactics and strategy reflects a deeper, more concerning trend: the Islamic State’s apparently increasing ambition to establish a consolidated territorial presence in the region. The group’s focus appears to have shifted from mere survival to a more structured approach aimed at territorial and population control and “governance.”

This is evident in the group’s recent nonmilitary activities, which were recently telegraphed by the Islamic State’s core organization, including its efforts to recruit and win favor among local populations. These involve both carrots and sticks. Around the town of Mucojo, which lies about 30 miles east of Macomia, IS-M has reportedly “banned certain haircuts, the sale of alcohol and the wearing of tight or tapered trousers, while encouraging people to practise daily prayers at mosques.”

Regional and Global Implications

The implications of the Islamic State’s resurgence in Mozambique are profound, not only for the country but also for the broader East African region. Cabo Delgado is home to several major liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects, and escalating violence there poses a direct threat to these critical economic assets.

The threat extends beyond immediate security and economic concerns. Heightened instability in northern Mozambique has already displaced tens of thousands of people, creating a rapidly worsening humanitarian crisis—and these dynamics are only likely to intensify in the coming months. Moreover, based on IS-M’s long-standing links with regional jihadist networks in Tanzania, Kenya, and South Africa, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), it will also likely have spillover effects into neighboring countries and broader sub-Saharan Africa.

The international community has a crucial role to play in addressing this threat. Even if the withdrawal of SADC forces is managed carefully, it will almost certainly precipitate greater violence and strengthen the Islamic State. However, resource constraints and competing SADC priorities in the DRC have influenced the decision to begin the drawdown.

What’s clear is that continued support for the Mozambican security forces is essential to countering IS-M’s advances and meaningfully mitigating its threat to regional stability. The governments of South Africa and Rwanda have pledged additional assistance in recent weeks, the latter with support from the European Union.

Support should not, however, be limited to military assistance. Building the capacity of local governance and improving economic opportunities, not to mention addressing how these are communicated to key audiences in Cabo Delgado, are critical components of the comprehensive counterinsurgency strategy that is required.

International donors and development agencies must therefore work in tandem with security forces to create and communicate a stable and resilient environment that can withstand the pressures of a resurgent Islamic State threat.

Managing the Threat

The current situation is almost certain to worsen in the coming months with the SADC drawdown, and the recent attack on Macomia is a stark sign of what may be to come. It is imperative that the international community be more proactive in supporting local efforts to counter this insurgency. With the winding back of regional partner interventions, failure to do so could have far-reaching consequences for the security and economic stability of East Africa. While no external parties can provide a solution to the threat posed by the Islamic State in Mozambique, they can work to keep it in check.

– Charlie Winter is chief research officer at the open-source intelligence platform ExTrac. He is an associate fellow of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism in The Hague and a member of the RESOLVE Network’s Advisory Board. He has a Ph.D. in war studies from King’s College London. Published courtesy of Lawfare.