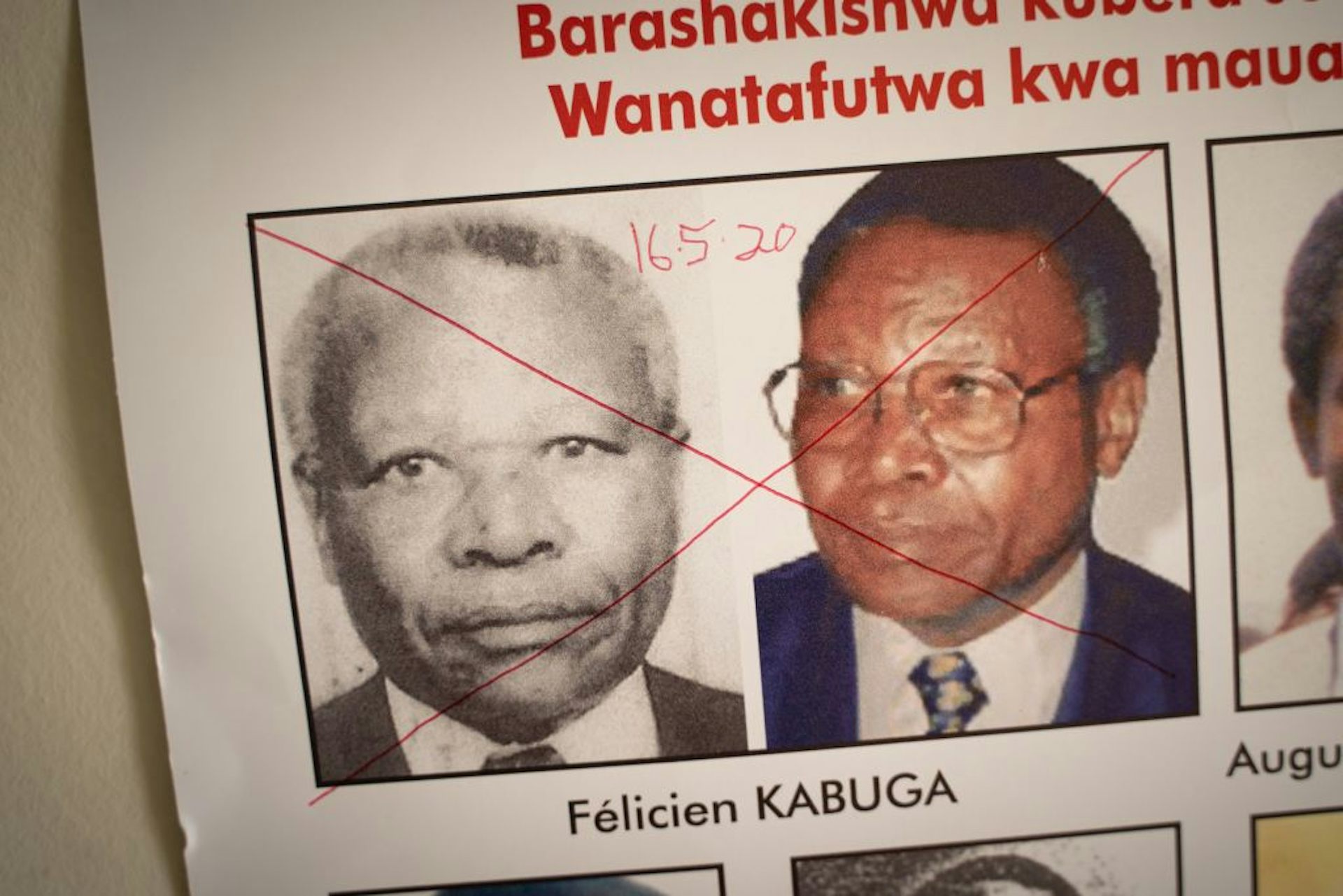

Félicien Kabuga, the Hutu financier of Rwanda’s 1994 genocide, has been captured after 26 years in hiding. More than 800,000 Rwandans, primarily Tutsis, were slaughtered by their countrymen in 100 days of genocide.

Kabuga was arrested by French police in a sting operation in a suburb of Paris on May 17. They were acting on an indictment by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1997. Despite a global arrest warrant accompanied by a $5 million bounty, Kabuga avoided authorities for 26 years.

He owned and operated Radio Mille Collines, which broadcast messages of hatred. This included the notorious command to “kill the cockroaches” before and during the genocide. He allegedly imported and distributed the hundreds of thousands of machetes that were instruments of the genocide.

Despite the arrest, there are a number of reasons that Kabuga’s case does not represent a simple triumph for justice.

First, the long anticipated trial that would shed light on how Rwanda’s genocide was organised may not come to pass. Kabuga is at least 84 years old. There is already a fight heating up about where he should be tried: France, Tanzania, or Rwanda. After this question has been resolved, we should expect that his attorneys will argue he is too frail to stand trial. Thus Kabuga’s advanced age and the slow speed of international justice mean that he may never see trial.

Second, his arrest revisits the contested success of transitional justice in Rwanda, and showcases the mixed record of international justice more generally.

The legacy of a tribunal

Based in Arusha, Tanzania, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was set up in 1994. It operated until 2015. It indicted 93 individuals, and heard 55 cases. Since its closure, outstanding work and cases are handled by the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Trials, which has branches in The Hague and Arusha. It handles only ongoing cases or outstanding warrants, and has no power to bring new indictments.

International criminal justice faces a number of criticisms. These include that it is slow and expensive, replicates colonial power relations and is overtly political.

In addition to these standard criticisms, during its working lifetime the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda faced multiple corruption allegations.

Kabuga was one of nine indicted individuals long at large, an ongoing reminder of the limitations of international criminal justice. Lacking their own police force, international courts rely on the cooperation of states to produce wanted individuals.

In Kabuga’s case, the capture was made possible by the investigative work of a special French office that pursues violators of international criminal law.

That the French followed up on this 26-year-old, cold, indictment is significant. International cooperation and institutional validation can have useful spillover effects for other international criminal justice institutions, specifically the International Criminal Court. It has struggled massively to convince member states to enforce its warrants.

Kabuga’s arrest, and the international cooperation that brought it about, is a reminder of the promise, and premise, that underwrote the tribunal. His alleged participation in the Rwandan genocide is the type of criminality that international justice seeks to prosecute: leaders and enablers who have not personally committed atrocity, but who were central to its deadly reach.

Kabuga’s arrest is thus also a victory against impunity. His trial should reiterate an insistence on rule of law norms making violations of international criminal law prosecutable.

Rwanda’s contentious transitional process

Accountability for international crime is a central component of “transitional justice”. This is a policy designed to substitute liberal, rule of law values in place of ethnic, nationalist, authoritarian or murderous rule.

In the case of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, “reconciliation” was embedded in the UN Resolution setting it up.

But Rwandan President Paul Kagame has rejected this model of transitional justice. Instead, a firm line is drawn between Tutsis, the victims of the genocide, and Hutus, the perpetrators of the genocide. This erases many facts, such as moderate Hutu victimisation or Tutsi-organised crimes.

Attempts to address facts outside of those officially sanctioned are decisively suppressed by the state. This has included imprisonment and assassination.

One of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda’s biggest failures was arguably its inability to challenge Kagame’s ethnically divisive narrative.

In the first years of its work, prosecutors began investigating crimes associated with the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the Tutsi forces led by Kagame. In retaliation, Kagame stopped cooperating with the court and had its prosecutor, Carle del Ponte, removed. No RPF members, or Tutsis, were ever indicted by the tribunal.

Kagame is often praised for his stewardship over Rwanda’s economic recovery. Increasingly, however, observers speculate that his authoritarianism will interrupt this economic success. More worryingly, scholars in the area fear that Kagame’s ethnicity-based governance risks future repetitions of cyclical ethnic violence in Rwanda.

Insistence on rule of law norms

In the wake of Kabuga’s arrest, some international criminal justice scholars have supported Rwanda’s call to have him tried in the country, instead of sending him to the tribunal in Arusha.

This call should be resisted.

Present-day Rwanda is a country in which opposition figures die – in jail or otherwise – with alarming regularity. International institutions as well as state governments should demand higher rule of law standards, particularly in a country that has been the recipient of sustained, multifaceted international assistance.![]()

Kerstin Carlson, Associate Professor International Law, University of Southern Denmark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.