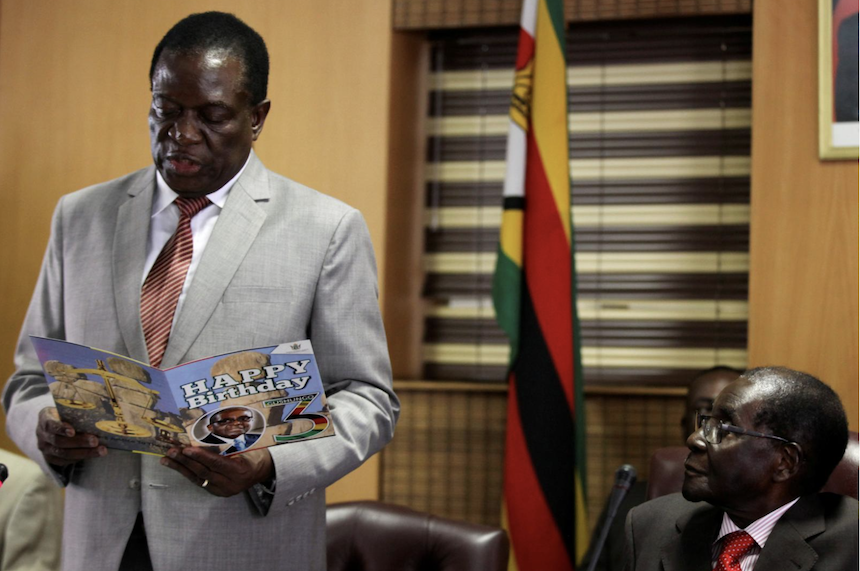

HARARE/JOHANNESBURG (Reuters) – In January, a photograph appeared in Zimbabwe’s media showing Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa enjoying drinks with a friend. In his hand was a large novelty mug emblazoned with the words: “I‘M THE BOSS.”

To supporters of President Robert Mugabe, the inscription bordered on treason. They suspected that Mnangagwa, nicknamed The Crocodile, already saw himself in the shoes of Mugabe, 93 years old, increasingly frail and the only leader the southern African nation has known since it gained independence from Britain in 1980. Those Mugabe supporters are not alone.

According to politicians, diplomats and a trove of hundreds of documents from inside Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organization (CIO) reviewed by Reuters, Mnangagwa and other political players have been positioning themselves for the day Mugabe either steps down or dies.

Officially, Mugabe is not relinquishing power any time soon. He and his ruling ZANU-PF party are due to contest an election next year against a loose coalition led by his long-time foe, Morgan Tsvangirai.

But the intelligence reports, which date from 2009 to this year, say a group of powerful people is already planning to reshape the country in the post-Mugabe era. Key aspects of the transition planning described in the documents were corroborated by interviews with political, diplomatic and intelligence sources in Zimbabwe and South Africa.

The documents and sources say Mnangagwa, a 73-year-old lawyer and long-standing ally of Mugabe, envisages cooperating with Tsvangirai to lead a transitional government for five years with the tacit backing of some of Zimbabwe’s military and Britain. These sources leave open the possibility that the government could be unelected. The aim would be to avoid the chaos that has followed some previous elections.

This unity government would pursue a new relationship with thousands of white farmers who were chased off in violent seizures of land approved by Mugabe in the early 2000s. The farmers would be compensated and reintegrated, according to senior politicians, farmers and diplomats. The aim would be to revive the agricultural sector, a linchpin of the nation’s economy that collapsed catastrophically after the land seizures.

Mnangagwa feels that reviving the commercial agriculture sector is vital, according to the documents. “Mnangagwa realizes he needs the white farmers on the land when he gets into power … he will use the white farmers to resuscitate the agricultural industry, which he reckons is the backbone of the economy,” a Jan. 6, 2016 report reads.

Mnangagwa did not respond to repeated requests for comment about the intelligence documents or the photograph of him holding the mug. An aide in his office said questions should be sent to the Ministry of Media, Information and Broadcasting Services. The ministry did not respond to questions.

Tsvangirai, a 65-year-old former union leader who enjoys broad popular support, told Reuters in an interview in June he would not rule out a coalition with political opponents, such as Mnangagwa, and wanted white farmers to come back into a “positive role.”

Asked about reports in the intelligence documents that potential coalition partners or their intermediaries had held secret meetings, Tsvangirai told Reuters in August: “I’ve never met with Mnangagwa’s people to discuss cooperation or coalition. There was an intention expressed by Mnangagwa’s people for us to meet to discuss various issues, but that meeting never took place.”

According to the intelligence reports, Mugabe got wind of Mnangagwa’s ideas about white farmers earlier this year. “Mugabe is totally against the idea of Mnangagwa being too friendly to the whites,” a report dated Feb. 27 says. “He fears that Mnangagwa will reverse the land reform by giving farms back to the whites.”

Mugabe’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

A spokesman for the British embassy in Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, said the UK was not involved in any plan for a coalition to succeed Mugabe. “The UK does not back any party, candidate, faction or coalition in Zimbabwe. It is up to Zimbabweans to choose who they want to govern them through a free and fair election.” The embassy said rumors and leaked intelligence documents were promoting disinformation.

The documents cover the gamut of Zimbabwean politics and contain material derogatory of all its major players, including Mugabe. A June 13 report said Mugabe was in “extremely poor health” and had told his wife, Grace, that “his days on earth are fast becoming less and less.”

Reuters has not been able to determine the intended recipients of the documents or their exact origin within the CIO. The intelligence agency officially reports to Mugabe but has splintered as opposition to his rule, which has lasted 37 years, has grown, according to two Zimbabwean intelligence agents interviewed by Reuters. The CIO did not respond to requests for comment sent to it through Mugabe’s office.

The intelligence reports say that some of Mugabe’s army generals are starting to swallow their disdain for Tsvangirai, who, as a former union leader rather than liberation veteran, has never commanded the respect of the military. The majority of senior military officers “are saying that it is better to clandestinely rally behind Tsvangirai for a change, and have secretly rubbed shoulders with Tsvangirai and cannot see anything wrong with him,” a report dated June 2 this year says.

A report dated June 13 this year says: “Top security force officials have been clandestinely meeting with Mnangagwa for the past few days to discuss Mugabe. They all agree that Mugabe is now a security threat due to his ill health.”

An army spokesman did not respond to written and telephone requests for comment.

ZIMBABWE‘S DECLINE

When Mugabe took power after colonial rule ended in 1980, he inherited an economy flush with natural resources, modern commercial farms and a well-educated labor force. Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere told him at the time: “You have inherited a jewel. Keep it that way.”

In his early years, Mugabe, a former Marxist guerrilla, won plaudits for improving healthcare and education, promoting economic growth and reconciling with Zimbabwe’s white minority, including farmers. But in 1998 Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change emerged as a serious threat to ZANU-PF, and Mugabe changed tack.

The tipping point came in 2000 when Mugabe approved radical land reforms that encouraged veterans from the fight for liberation to occupy some 4,000 white-owned commercial farms. At least 12 farmers were murdered. Most fled with their title deeds to countries such as South Africa, Britain or Australia. A few remained in Zimbabwe, where they became active in opposition politics.

After Mugabe loyalists and inexperienced black farmers took over the land, the economy went into freefall. Before 2000, farming accounted for 40 percent of all exports; a decade later the figure was just 3 percent.

GDP almost halved from 1998 to 2008. The central bank began printing money to compensate and hyperinflation took hold. At its height Zimbabweans were buying loaves of bread with Z$100 trillion notes.

Mugabe was forced to cede some control in 2009 to a unity government that scrapped the worthless Zimbabwe dollar in favor of the U.S. dollar. Economic growth resumed. But since Mugabe regained outright control in a 2013 election, growth has faded and the central bank has begun issuing “bond notes,” a domestic quasi-currency that is already depreciating.

It was against this dismal economic backdrop that potential successors to Mugabe began planning for his departure.

THE CROCODILE STIRS

According to the intelligence files, Mnangagwa’s overtures to Tsvangirai and white farmers became apparent in early 2015 amid bitter strife within the ZANU-PF party. On one side is Mnangagwa’s faction – dubbed “Team Lacoste” after the crocodile-branded French fashion chain. On the other is G40, a group of young ZANU-PF members who have coalesced around Mugabe’s 52-year-old wife, Grace.

In March 2015, the intelligence documents make the first mention of Mnangagwa meeting white farmers, including Charles Taffs, a former president of the Commercial Farmers Union (CFU), the farmers’ professional association. Some of the gatherings were boozy affairs, according to the intelligence reports.

“Mnangagwa had a slip of the tongue this week that angered Mugabe and Grace, when he told people who were around that ZANU-PF rigged the elections in 2013, this being said while under the influence of liquor,” a March 19, 2015 report reads.

“His drinking problem is worsening these days, being put down to the fact that certain white people, who include Taffs … have become friendly with Mnangagwa and have spoiled him with gifts of whisky. It is now party after party for Mnangagwa and his friends because he is provided with free whisky, supplied without any hitches and in great quantity.”

Mnangagwa and the information ministry did not comment. One of the vice-president’s allies, Christopher Mutsvangwa, rejected the reports about Mnangagwa’s alcohol consumption. Mutsvangwa told Reuters that Mnangagwa is “never a heavy drinker. Indeed, he is very disciplined about taking alcohol … I have hardly seen him drinking in recent times.”

In an email, Taffs, the former head of the farmers association, told Reuters: “I have met the VP (Mnangagwa) on numerous occasions in my past capacity as president of the CFU, but have never had drinks with him, neither have I ever given him whisky or any other gift.”

Taffs rejected claims in the documents about plans for a unity government. “I have never been involved in any plans or discussions for the formation of an unelected coalition government.”

MASSACRES

The problem for Mnangagwa is that, if he ran for president, it is unlikely he could win an election in his own right, according to political analysts. He holds impeccable credentials from the struggle for liberation, having fought alongside Mugabe against the loathed white-minority government of what was then Rhodesia. However, his reputation suffered in the early 1980s, when Zimbabwe’s army brutally suppressed dissent, mainly in the western province of Matabeleland North.

In the so-called Gukurahundi crackdown, the army’s North Korean-trained Fifth Brigade killed an estimated 20,000 people, most of them from the minority Ndebele tribe. Mnangagwa was state security minister at the time. He has denied any involvement in the massacres, and did not offer fresh comment; but in the eyes of many voters he is still too tarnished to be electable.

Mnangagwa failed to win a seat in parliamentary elections in 2000 and 2005, but was appointed by Mugabe to unelected seats and became parliamentary speaker in 2000. He has served as vice-president since 2014.

Tsvangirai beat Mugabe in the first round of an election in 2008 only to pull out of the second round because of violence. Mnangagwa, according to people in his camp and Western diplomats, sees in Tsvangirai a politician who can deliver broad public support to complement his own connections with powerful political and military interests.

Mnangagwa and the Ministry of Media did not respond to requests for comment.

MILITARY MIDDLEMAN

Mnangagwa’s supporter Christopher Mutsvangwa heads the Liberation War Veterans Association, whose members include veterans who expelled the white farmers nearly two decades ago. He told Reuters that Tsvangirai could have a role in government if Mnangagwa became president.

“Why can’t there be an accommodation with Tsvangirai?” the 62-year-old Mutsvangwa said in an interview in Harare, in answer to a question about whether there could be a coalition government led by Mnangagwa and Tsvangirai. He said a partnership would be unifying in a country with deep political divides. “If they decide to coalesce that’s good because they represent solid historical constituencies.”

According to the intelligence reports, Mutsvangwa is a middleman between various parties involved in a possible coalition government.

“Mutsvangwa is more than prepared to make sure that Mnangagwa and Tsvangirai strike up a coalition. He says that the country needs no election at this stage, just a change of leadership and structure of government,” a Feb. 22 intelligence report says.

When asked about the deal described in the intelligence documents, Mutsvangwa said elections must be held in line with the constitution and that an elite could not rule “bereft of popular legitimacy.”

He said it was his duty to work with all political sides, and that he had “reached out” to Tsvangirai and the “post-colonial white diaspora.” He added that as chairman of the war veterans he wanted to ensure a “peer comrade” takes over from Mugabe and that Mnangagwa could naturally aspire to the highest office.

In a statement in 2016 the war veterans, many of whom are now nearing retirement, accused Mugabe of being “ideologically bankrupt” and ignoring the plight of Zimbabwe’s masses as the economy imploded. Mutsvangwa said his only aim is rebuilding the economy and country.

For Tsvangirai, a deal with Mnangagwa may be the best shot at the power he has craved for decades. Speaking to Reuters in June, Tsvangirai did not rule out a coalition deal.

“For the moment, it’s an electoral contestation but post-that, who knows? What are the two things that are important – stability and legitimacy. That is the only way in which you can move the country forward,” Tsvangirai said.

“CHOSEN ONE”

Amid all the jockeying for position, one influential figure is Catriona Laing, the British ambassador to Zimbabwe. According to four people with direct knowledge of coalition-related discussions about post-Mugabe rebuilding, Laing favors Mnangagwa to succeed Mugabe.

In addition, three Harare-based Western diplomats said Laing, a development expert rather than career diplomat, supports the idea of a coalition government, believing such a move is needed to maintain Zimbabwe’s stability.

Laing declined to be interviewed, but the British embassy strongly rejected these claims. It said Laing last met Mnangagwa in May 2016 for routine policy discussions. “The ambassador has not met with the VP or anyone connected with him to promote the formation of a coalition government,” said the embassy spokesman. “The UK unambiguously rejects claims that it is pushing for a particular candidate to succeed Mugabe.”

Mugabe’s wife, Grace, suspects that the British support Mnangagwa, according to a Nov. 16, 2015 intelligence report. It says: “Grace reckons that the Mnangagwa camp is full of sell-outs who are working with the British to remove her husband from power.”

And a report dated March 2, 2016, says: “Laing, whose mouth is ‘too big’, has now been telling other embassies that Mnangagwa is the chosen one to succeed Mugabe.”

The documents give no verifiable evidence for that claim and Reuters could not confirm it.

Whether any plan for a coalition comes to fruition remains to be seen. Even with the support of some army generals, Mnangagwa will face significant opposition from the president’s wife, Grace, and the G40 group supporting her in the struggle to assume the seat Mugabe has occupied for nearly four decades.

In July, Grace challenged her husband to name his successor, leading Mugabe to tell a political rally he was not stepping down and “not dying.”

“I will have an ailment here and there, but bodywise, all my internal organs … very firm, very strong,” he said, as he leant against a lectern.

Grace Mugabe’s G40 faction suffered a setback this month when she was accused of assaulting a 20-year-old South African model with an electric cable in a luxury Johannesburg hotel. Grace Mugabe made no public comment on the incident, but her supporters said the allegations were unsubstantiated. Pretoria granted Grace Mugabe diplomatic immunity, allowing her to avoid prosecution; the Democratic Alliance, South Africa’s main opposition party, is challenging that immunity in court.

Some diplomats in Harare say the United States and European Union are opposed to the idea of Britain backing Mnangagwa because they are concerned about being ostracized by ZANU-PF and its G40 faction should events unravel and go against Mnangagwa.

The British embassy in Harare said it had taken no steps to influence the succession to Mugabe, and that rumors were spreading disinformation. A spokesman for the U.S. Embassy said it did not back any candidate or party. The European Union ambassador in Harare, Philippe Van Damme, said in an emailed statement that the bloc, including the UK, does not support any political party or faction in Zimbabwe, but does support reforms “no matter who delivers them.”

By Joe Brock and Ed Cropley. Editing By Richard Woods