Election management bodies are essential democratic institutions. To deliver national polls effectively, they need to be properly resourced, impartial and free from government or malicious interference.

Independent election bodies established in the 1990s played an important role in the early deepening of democratic values across Africa. As most countries started expanding rights and freedoms and strengthening the rule of law, the bodies coordinated successive multi-party elections. Their performance could be weak or inconsistent. But elections became routine and accepted as a necessary means to legitimise political power.

However, advancing and consolidating wider democratic gains on the continent has proved more difficult.

Since the mid-2000s the headwinds have got stronger. “Democratic backsliding” refers to the hollowing out of democratic institutions, rights and practices by elected governments. Research organisations which measure democracy have tracked declines across multiple democratic indicators in Africa and around the globe.

Attahiru M. Jega, former chairman of Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission, and I set out to determine whether democratic backsliding had weakened Africa’s election management bodies. As scholars with professional backgrounds in election administration and international electoral support respectively, we see this question as critical to understanding the context in which election bodies operate. It’s also vital in developing strategies to strengthen them.

We found that African election management bodies today face complex challenges which are not simply a product of democratic backsliding. Increasing their effectiveness therefore requires a much broader approach to safeguarding their independence, building their capacity, and encouraging all stakeholders to support their work.

The study

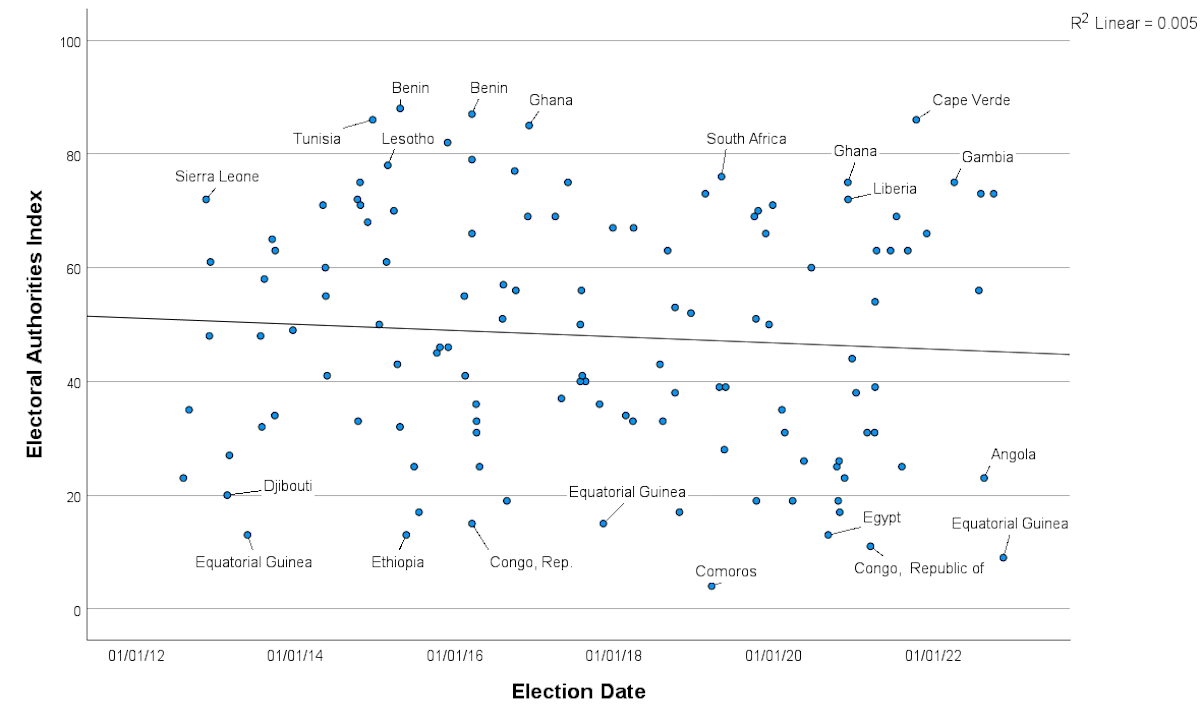

Our study reviewed the performance of election management bodies in 48 African countries between 2012 and 2022. This is captured in the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) dataset, produced by the Electoral Integrity Project. The global academic think tank, based at universities in Canada and the UK, evaluates the quality of elections held around the world.

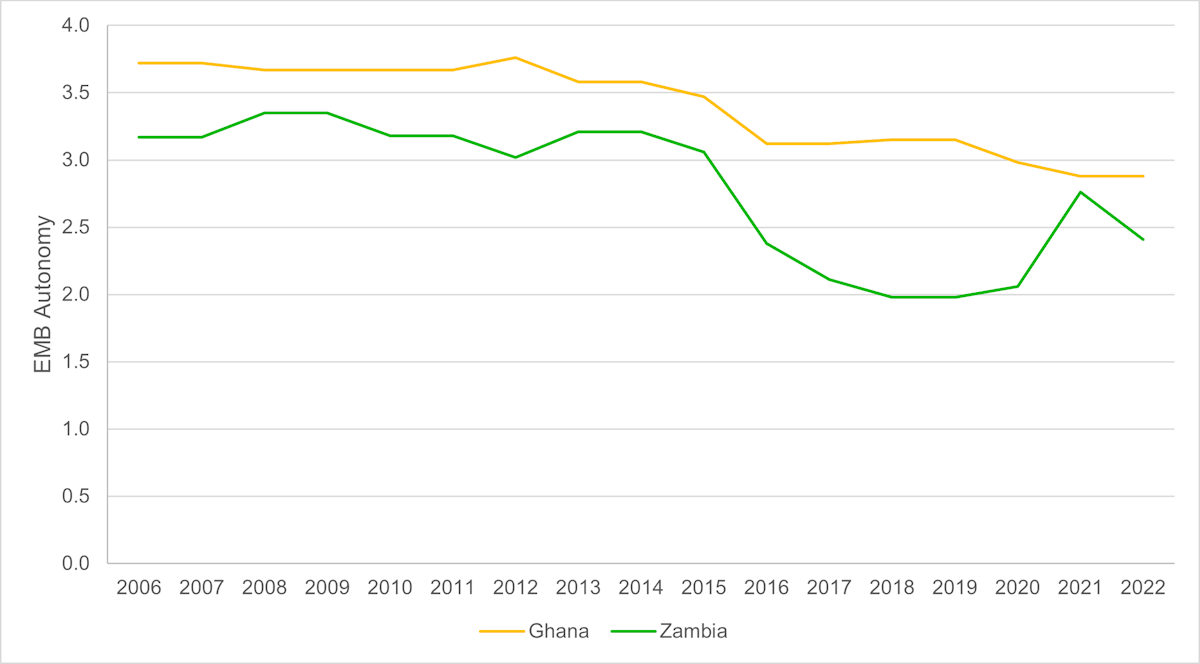

We also analysed election body autonomy data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project. This is produced by an independent research institute at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Election body autonomy is a narrower measure compared to those in the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity dataset. However, it offers more granular insight into what has happened in 51 African countries since 2006.

We concluded with case studies of Ghana and Zambia to investigate the factors affecting the autonomy of their election bodies.

If democratic backsliding was directly affecting election management bodies, we would expect to see downward trends in the data. Instead, they show wide variation in the bodies’ performance and autonomy across Africa. Our case studies show that the bodies face many challenges that cannot be explained by democratic backsliding alone.

Diversity over decline

The Perceptions of Electoral Integrity data (Figure 1) shows a striking diversity of performance. This echoes global patterns of divergence in election quality rather than institutional decline linked to democratic backsliding.

The V-Dem data on autonomy confirms the wide variation in election body experiences across Africa. Between 2006 and 2022, an almost equal number of countries experienced net declines as net improvements. Nor was the path always straight. In many cases, election body autonomy fluctuated over the 16-year period. This suggests independence must be continuously cultivated.

Eight countries showed sharp declines between 2021 and 2022. These might be linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, which created opportunities for governments to restrict democratic rights.

Constraints on autonomy

The numerous cases of improvement support arguments that democratic backsliding is not an inexorable trend in Africa. Nonetheless, half of its electoral bodies had experienced declines in autonomy, so there is clearly no room for complacency.

To investigate possible drivers of decline, we looked at Zambia and Ghana. These countries have a track record of peaceful elections. They have also had changes of power between different parties since the 1990s. However, the autonomy of their election bodies has declined over the last decade (Figure 2).

Zambia has been described as experiencing “distinct, observable democratic backsliding” under the ruling Patriotic Front between 2011 and 2021.

It is clear from international and domestic election observer reports that this undermined the Electoral Commission of Zambia ahead of the 2016 and 2021 elections. Opposition parties and civil society were frustrated by the commission due to its:

- lack of transparency

- failure to consult them

- inconsistent enforcement of electoral rules.

Still, the commission did deliver elections in 2021 which were credible enough to enable a peaceful handover of power. We also found that the Patriotic Front’s grip on power tended to worsen long-standing problems rather than create new ones.

For example, Zambia’s weak electoral framework gave the president significant powers over the commission’s leadership and finances. Nor did it clearly define key electoral rules and procedures. A lack of administrative capacity has also hampered the commission since it was established in 1996.

Our analysis of Ghana suggests that declining electoral body autonomy has not been a product of direct interference by elected governments. Instead, growing polarisation between the main political parties was the dominant factor.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Electoral Commission of Ghana built cross-party consensus on delivering elections through a dedicated committee. However, this forum became less effective over time. Partisan disagreements over the commission’s decisions increasingly played out in court and in the media.

Disputes over election procedures and the appointment of commissioners became politicised. Opposition parties routinely tried to undermine the commission’s credibility.

The legal challenges also tarnished the commission’s reputation for competence. Over time, this had a negative effect on public perceptions and the operational independence of the electoral body.

Complex challenges require coordinated responses

Democratic backsliding remains a concern in Africa and globally. But our study shows that the challenges African election bodies face are multifaceted. It is not just anti-democratic leaders that limit their autonomy and effectiveness. Weak legal frameworks, insufficient capacity and political polarisation also play a role.

New media technologies and health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic have also made the operating environment even more complex.

This makes it ever more urgent for election bodies to build consensus over election delivery. They must also improve institutional capacity and transparency. Stakeholders, including policymakers, political parties, civil society and the media, must do all in their power to foster electoral integrity.