The Transaqua Project is a big, ambitious initiative to replenish the waters of Lake Chad, a fresh water inland lake in Central Africa.

It involves 12 countries working together to build a 2 400 km canal to move about 100 billion cubic metres of water from the River Congo to the lake every year. The Lake Chad basin supports more than 20 million people.

If accomplished, the Transaqua Project will change the face of Africa – for better or for worse. But like other regional or transnational projects on the continent, it may be delayed or abandoned if national politics are ignored.

The replenishment project, mooted over 30 years ago, involves building several dams along the length of the canal.

The dams will potentially generate 15 to 25 thousand million KWh of hydroelectricity and irrigate 50 000 to 70 000 km2 of land in the Sahel zone. This will stimulate development in agriculture, industry, transport and electricity for up to 12 African countries.

But the project is not immune from criticism. Some argue that claims that the lake is shrinking are exaggerated. Others argue that the plan poses serious environmental risks.

It is difficult to determine whether the canal will address why the lake is drying up. And who benefits, and what the benefits will be to each country still remain unknown. It’s also possible that disagreement within and between countries could scuttle the project.

A memorandum of understanding for a feasibility study and the construction of the project was signed in December 2016 by the Lake Chad Basin Commission and PowerChina, the Chinese state engineering and construction firm.

The commission represents the interests of the 12 countries involved in the project and is guided by The Water Charter. This is the main instrument that outlines the mechanisms for dispute settlement.

The Charter, though, focuses on dealing with conflicts between countries rather than within them.

It is therefore worrying that the most important country in the project, Nigeria, faces internal challenges that may affect the project.

The long term nature of the project demands that the participating states are relatively stable in political and economic terms. Nigeria, Cameroon and Libya account for 78% of member contributions to the commission. Libya is currently seen as a failed state, so the focus is on Nigeria to offer political direction for the project.

Nigeria mirrors the challenges

Nigeria plays a powerful role as a regional leader and a major financial member of the Lake Chad Basin. Nigeria also pays 40% of the commission’s membership contributions of €6,275,906.90 (2013 budget).

Three political issues in Nigeria could affect the project.

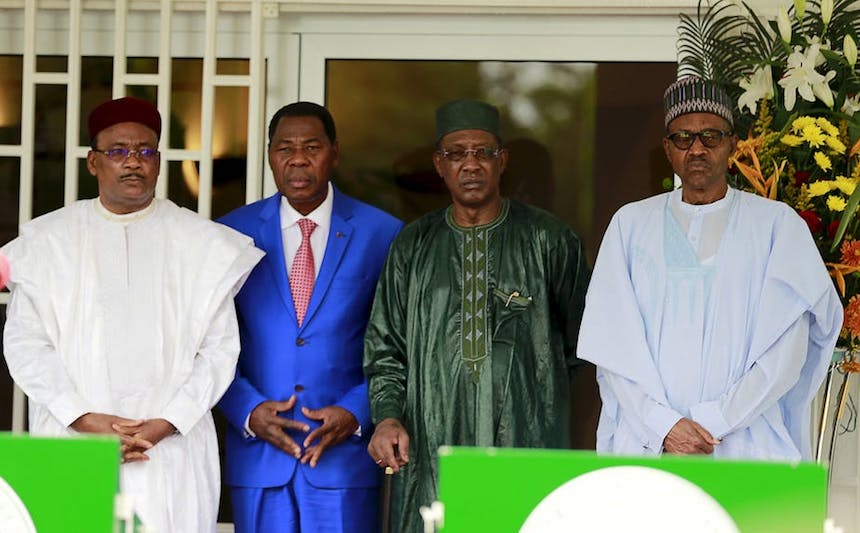

The first is that President Muhammadu Buhari has had an important influence on its progress. Since he assumed office in May 2015, four milestones have been reached:

- Nigeria ratified the Water Charter, five years after it was signed.

- Nigeria signed the Charter for the Lake Chad Basin into law.

- PowerChina and the Commission signed the memorandum of understanding.

- PowerChina and Italian firm Bonfica Spa signed a deal to conduct the feasibility study and build the Transaqua project.

If Buhari’s influence wanes, the project could lose momentum.

The second political issue is that Nigerians will go to the polls again in 2019. Buhari’s health challenges, combined with the country’s economic and political challenges, have reduced his approval ratings from 67% when he was elected to 44% in 2016.

The re-organisation and re-emergence of the opposition People’s Democratic Party gives voters a strong alternative, especially in parts of the country without an alternative political party that can compete with their political structure and finances.

That party, which was in power for 16 years, might not be able to meet the financial or security commitments to the water project because of their past history in government.

The third factor relates to institutional politics. The executive secretary of the Lake Chad Basin Commission, Abdullahi Sanusi Imran, has stated that the Transaqua idea “is much more appropriate for the situation of the Lake Chad than all other alternative solutions.” But an informal conversation with a senior Nigerian government official in the course of research fieldwork expressed concern about the choice of the Transaqua idea over other alternatives.

These alternatives were presented in the National Audit Report of Nigeria as part of the Joint Environmental Audit report on the drying up of Lake Chad: a report prepared by the Supreme Audit Institutions of each of the states for the African Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions. Dissenting positions can create unnecessary friction between government agencies and make it difficult to coordinate actions.

So what should come next?

Amendments to the Water Charter to provide for addressing intra-national political challenges are vital; a task for the African Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions, the Lake Chad Basin Commission and the Supreme Audit Institutions in their respective national domains. States could be required to outline how they might solve potential political challenges in their domains. Expectations and responsibilities should be built into the Charter beyond negotiations and gentleman’s agreements.

The Lake Chad Basin Commission, political office holders and government institutions should work together to make the project’s objectives a key election issue in subsequent elections.

![]() Intra-national and national politics cannot be ignored. But the project should also harness local knowledge and experience, and recognise local conditions so that it’s accepted by everyone.

Intra-national and national politics cannot be ignored. But the project should also harness local knowledge and experience, and recognise local conditions so that it’s accepted by everyone.

Adegboyega Adeniran, PhD Candidate, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University and Katherine Daniell, Senior Lecturer, Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.